“Choreography is the boundary within which you improvise.”

Jennifer Mascall & Emma Metcalfe Hurst

Interview for Coming Out of Chaos: A Vancouver Dance Story

September 6, 2019

Jennifer Mascall, Founder of MascallDance, founding member of EDAM, dancer in Coming Out of Chaos (1982)

Emma Metcalfe Hurst, Karen Jamieson Dance Archivist/Creative Director of Coming Out of Chaos

This oral history interview has been edited for length, clarity, and accuracy

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, let's get started with the first question: what is your background entering into contemporary dance? Could you please share your dancing story.

Jennifer Mascall: I began dancing at fifteen years old at the school of Toronto Dance Theatre. Then I went to York University and was in the first graduating class. I studied Graham technique six days a week and ballet. Sandra Neels came somewhere through that and started teaching Cunningham. Other influential studies there were experimental music, South Indian singing, Chinese theatre, East Asian art history, and classical Greek. The most inspiring catalyst was Selma Odom, who later started the Graduate program there. She taught dance history and criticism and she introduced me (literally and through studying) to all the choreographers in downtown New York City. She and I edited a dance review, where I first began writing dances. They were the post-modernists, not the modernists, not like Nikolais, Graham, Cunningham – it was the people post-Cunningham. We went to New York City and saw their work. We met with critics talking and writing about experimental work. Selma brought people to York University to teach us, and a lot of the conceptual work could be translated by ideas. So, for example, when she brought up Marcia Siegel to teach us, Marcia brought a score from Kei Takei and one from Steve Paxton. We were able to learn physically the conceptual repertoire of the experimenters who were the artists that I was drawn to.

In the training at York University, there was a sense of how exciting Graham technique was. However, I was completely drawn to non-traditional work. A visiting guest, Gus Solomons, introduced me to site specific work. One year, David Rosenboom brought in Frederic Rzewski who played his composition called Coming Together (1971) about the Attica prison break. At the time I thought it was the most exciting thing I'd ever heard. The text to the piano score was from a quote by a surviving prisoner, Richard X. Clark, who said when he was released, “Attica is in front of me.” I made a dance to the ten-minute version of it. That was the first choreography I ever did, for a theatre. 1

My first composition was a dance in a video arcade in California in 1973. The first grant I ever received was from the International Women's committee and was to put on seventeen site-specific performances in the month of June in 1974. The site-specific collective was called GRID. I collaborated with Johanna Householder in particular, and Joan Phillips, who ran the performances as I was the movement coach at the Stratford Festival in Stratford, Ontario that summer. There was a formative host in downtown Toronto called 15 Dance Lab run by Lawrence and Miriam Adams. 15 Dance Lab was the catalyst for the Independent Dancer movement in Toronto and with Elizabeth Chitty, I published SPILL, an influential newspaper that was an outlet for dance conversations. 15 Dance Lab produced my first solo concert in 1975 and throughout the ‘70s they produced five shows of my work, a total of 10 works. With 15 Dance Lab, A Space Gallery, Musicworks, and Art Gallery of Ontario there were possibilities for work. The second grant I received was a $2000 short term Canada Council grant and I lived on it for two years in New York City and danced in Lazy Madge, a project of Douglas Dunn. That is a sketch of the landscape before I came to Vancouver.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Wow. Yeah, that’s a lot!

Jennifer Mascall: Here is how I got to Vancouver: In 1977, from New York City, Ulla Koivisto and I made Fatty Acids and brought it to the Dance in Canada Conference in 1977 in Winnipeg. This conference was a pivotal moment in Canadian dance history. It would be one worth writing about. There had been a design by the funding bodies to develop Canadian dance through funding a company / companies in each major city. At this conference, it was clear there was a host of really brilliant mavericks who were taking dance in a different direction and could not be overlooked. The following year [1978], Grant Strate initiated the choreographic seminar with Robert Cohan and that is where I met Karen Jamieson.

The Dance in Canada Conference in ‘78 was in Vancouver and the piece I took was called Q/O, with Peggy Baker, Terry Crack, and myself. Richard Rose did the lighting. It was a statement on virtuosity and pedestrian dancing which was an issue in 1978. After that conference, I took a two-week intensive in contact improvisation with Peter Bingham, Helen Clarke, and Andrew Harwood who had a company called Fulcrum out of Western Front. At the Fulcrum intensive, I met Sara Shelton Mann and later that fall, Fulcrum, Sara, and I toured across Canada to Montréal, Toronto, and Halifax after ‘78, so I had made a connection with Peter Bingham who worked in Vancouver.

From the choreographic seminar [in 1978, a group of us emerged: myself, Susan MacKenzie, Paula Ravitz, and Denise Fujiwara, who founded Toronto Independent Dance Enterprise. So similar to Grid and similar to EDAM, it was a group of independents [and we called ourselves TIDE]. We did a tour in September ‘78 to Edmonton, San Francisco, and Victoria. In Vancouver, TIDE performed at the Western Front where Susan McKenzie and I performed Unicycle Blues.

In the following year, 1979, Sara Shelton Mann and I worked on Smashed Carapace in San Francisco. We also had a residency at Le Groupe de la Place Royale and that was where I met Ahmed Hassan. Smashed Carapace toured Halifax, Quebec city, Montreal, Toronto, Ottawa, Edmonton, Calgary, Vancouver, and Victoria. SFU was up on the hill in Burnaby at that time [1979], and Murray Farr had developed an international performance series that had no competition so everybody went there to see new work. We performed there and at the Western Front, and Sara Shelton Mann continued on to San Francisco and started a performance company called Contraband. I stayed here, in Vancouver, and immediately started dancing with Paula Ross.

So, arriving in Vancouver I knew Peter Bingham, Helen Clarke, and Karen Jamieson. As I surveyed the dance scene, it seemed healthy and inspiring as the choreographers were predominantly women and women who had children. At the same time, the funders here in the province and the city were not yet funding independents. The reason I feel it is pertinent [to mention] is that I fell in love when I got to Vancouver and was looking for a way to stay here. That is another potent topic to write about – women, dance, artists, love, and careers.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Having kids, and being a mother too. Yeah, so we got to Vancouver. That was in 1980...?

Jennifer Mascall: 1980. I started working with Paula Ross, and I worked with her for two-and-a-half seasons, and then I was fired. I had an impression that there was no independent movement here and I had enjoyed a decade of being an independent dance artist. What was a completely natural thing in other centres of dance didn’t seem to exist here.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Do you think there were increased pressures to professionalize? To have a company, or create and register as formal societies?

Jennifer Mascall: In Ontario around 1977, the provincial government accepted that people could be dance artists without dancing in companies. Grants had already been made available. In BC, the granting bodies would only accept a non-profit society. So, in '82, I started a nonprofit society called Mascall Dance.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Okay. That’s the answer to one of my questions. I was doing some preparatory research for this interview and there were two conflicting dates that came up for the formation of your company: 1982 and 1989.

Jennifer Mascall: Paul McNeil, who was a friend of Grant [Strate's], was a lawyer and someone who had been in the York dance department when I was there. He generously said he'd just do it for me. Anytime I did work outside of EDAM, I was paid through Mascall Dance – Commissions from TIDE, Halifax Dance, Mountain Dance, Dancemakers, touring grants for Scandinavia and Europe, etc. Then in 1989, when Lola [MacLaughlin] and I started working apart from EDAM, it was already there, active. So, it became my full-time–

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: –focus.

Jennifer Mascall: Yeah.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: From that point onwards. Okay. So, if you arrived in Vancouver around 1980, then Coming Out of Chaos must have been one of the first collaborative projects that you were involved with?

Jennifer Mascall: 1980 is when Lola [MacLaughlin] and Tony Giacinti graduated from Simon Fraser as the first two dancers. I went to see her graduation project and it was on Hastings Street, upstairs across from where Woodwards is now, in this kind of derelict studio, and she did a piece called Brain Drain which I found totally brilliant. I thought, Okay, it's going to be alright in Vancouver. So, she and I started collaborating, and we did two pieces. One was part of a series at Savannah [Walling] and Terry [Hunter's] studio, Terminal City Studio on Carrall Street. Other initial collaborations were with Peter Bingham, Lola Ryan. At the Western Front I started running a performance series once a month – Out Front, maybe? I then... when did Coming Out of Chaos start rehearsing? I only remember I was in Toronto working on a solo show...

(1) Jay Hirabayashi, and Helen Clarke.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: We're still trying to figure it out. I think we've gotten closest to fall of '81, and then I think in the conversation that you and Savannah [Walling] were having, you suggested that it might have started even earlier?

Jennifer Mascall: No, I think not.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Maybe it would have been like December ‘81? Because the first performance was in August ‘82.

Jennifer Mascall: '81.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah.

Jennifer Mascall: I see. Okay. So, then then in... [pause, counts on fingers]

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: [laughs]

Jennifer Mascall: I went and worked with Judith Marcuse in Toronto and she had chosen a number of mature dancers, meaning thirty-year-old dancers from many different points of view, and did a piece called Currents using Toronto people, Montréal people, and Vancouver people, and that was in, I think September maybe – September, October '80. Then I stayed in Toronto and I choreographed a piece, Piebald and Duff with TIDE, and during that time Karen [Jamieson] called and said: Do you want to be part of something? Do you want to be part of it? And I said, Yes, I do. When does it start? She said, Well, it starts now. And so she worked with Barbara Bourget for that time until I was able to return to Vancouver. Does Barbara [Bourget] remember that?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: That's what Barbara confirmed.

Jennifer Mascall: So, Barbara [Bourget] was there first, and then I started – for some reason I think it was in the new year.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: I think Barbara [Bourget] said she was only there for about two weeks.

Jennifer Mascall: Yeah, I think there was a short rehearsal period. When I came back [to Vancouver], there was a lot of dance projects going on and Coming out of Chaos was only one of them. We were all trying to work together because we knew we wanted to start this thing that wasn’t a dance company. Then in '81, but possibly it was after the Coming Out of Chaos tour, I was in Toronto for three months doing a piece called No Picnic. So, if it was '81, then I would have started in the January part, but during that same time – I can't fathom the scheduling... Perhaps we didn't rehearse all-day, every-day because I was choreographing non-stop, and made four pieces, and EDAM did its first concert right in the middle of Coming Out of Chaos rehearsals. We were supposed to do it at the Firehall [Arts Centre] and the Playhouse [Theatre] and something happened at the Firehall, so we had to move to the Waterfront [Theatre]. I think we provided buses or transportation for the audience. And this [EDAM] concert at the Waterfront had eleven performers: Helen Clarke, Patti Powell, Laurie Indyke, and another performer, as well as all the EDAM people. Ahmed [Hassan] was in Vancouver by then. Barbara Bourget was in a piece in that show with three women (myself, Patti Powell, and Barbara Bourget) and a refrigerator. And she remembers all of EDAM on stage doing an improvisation. Then, throughout that year, I think there was an EDAM performance at The Dub Club. What I remember about the improvisation between me, Peter Bingham, and Lola Ryan at the Playhouse was Lola Ryan following a speck of dust that was visible because of the lighting, and she was improvising with it. It was very, very funny... So, all of this was taking place during – or maybe there were gaps in the rehearsal of Coming Out of Chaos. We were meeting and talking about EDAM, and forming it, and all collaborating with each other in as many different ways as we could.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Maybe this is jumping ahead a little bit, but the Coming Out of Chaos group, you all went on to form EDAM shortly after.

Jennifer Mascall: Well, we became a non-profit in 1982. And got a grant and did our first piece as a non-profit called Run Raw: Human Deviation (1983).

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, okay. We'll come back to that. Thanks for outlining all of the activity going on at that time. Would you be able to describe and paint a picture of what the creative atmosphere was like in Vancouver?

Jennifer Mascall: Because I was new, [I got] this fresh glance. [Being] new... I felt there must be a way to not be stifled because you had to start a company, so that's why EDAM happened, to create a structure for independents. I didn't want to have my own company, and have dancers following only my direction. I wanted us to be working like equal artists together. We had to do something about that. At the same time, Simon Fraser [University] had this scene, what seemed to me a really lively art vision for their performance series. The Western Front, to me, because that's where I went and where I did contact [improv], seemed to be the centre of the art world. The curators and programers there seemed to know artists from all over the world, they had a vision. It [was] like, they're really doing things!

My interest in Paula Ross – when she asked me to dance, she came to see the piece we did, Smashed Carapace, and she said she was looking for a dancer, and I said, I'd love to. The reason I said that was because she had done a famous piece called Coming Together which was the long version for the Rzewski piece mentioned earlier about the Attica prison break.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Amazing. How serendipitous. Was there a strong sense of community at the time? From what you've said so far, it sounds like community was an inherent part of it all: all of these collaborations that were going on, and all of these studio spaces where you were able to foster this community, and work together, and learn about each other's practices, and develop your voices.

Jennifer Mascall: The words you are using are nothing like how we were thinking at the time. It was just: Here we are. What can we do? There's the studio. You can use the Western Front anytime you like. Here you are. You're a dancer. I like you. I like your dancing. Let's do a piece. It was more like that.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Organic, not intentional.

Jennifer Mascall: There was no sense of, let me try and find my voice, or, let’s build community. It was more, let's just do work. This is what we're doing.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Let's produce. Yeah. Were there any common interests or themes that started to arise out of these environments that you were involved in? Obviously, there was contact improv...

Jennifer Mascall: The dynamism of EDAM was that everyone was interested in very different things...

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Definitely. So, you touched on this, but the next question is: where were you drawing your personal influences from? I think the question that you posed: how does the body speak? Would be a good spot to unpack a bit, if you could?

Jennifer Mascall: Well, for some reason – and I don't know where this comes from, but I had the point of view at that time that the world of dance was small enough for us to get to know most of it. I was very interested in the development of visual art, and the development of music, and why did dance feel behind? That's what it felt like to me – it wasn't behind, it was just beside, but I kept doing comparisons: hey do that in music, so let's do that in dance. They do that in visual arts, so let's try that. That kind of thing. So, most of my influences came through looking at the other art forms and how it made a lens on what I knew about dance.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, you were taking a more interdisciplinary approach.

Jennifer Mascall: Not necessarily in that the work didn't look interdisciplinary, but it looked like they're thinking – why do they think like that, and we don't think like that? Why don't I think like that? Let's try that in dance! But that didn't mean that I was collaborating with a visual artist, I was just trying to understand how they had arrived at [different] kinds of forms of thinking.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Right, interesting. Going back to the first question and you painting the scene in New York at that time: the New Music scene, the visual arts, and the scores, was there a Fluxus influence on dance or choreography?

Jennifer Mascall: I didn't think like that at the time. But yes, yes it was totally happening.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: No?

Jennifer Mascall: Not at all. No, I didn't, but I bet the Western Front people would have thought that.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: What were some of the other driving forces influencing dance production at that time? So, funding bodies (which we've talked about), but also social movements, anti-institutional sentiments...

Jennifer Mascall: I was too new to the scene to know what was motivating it..

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. And could you describe what the funding situation was like in Toronto at that time? Did it differ from BC?

Jennifer Mascall: In Ontario in 1975, I was the first dance artist-in-residence in schools. The Ontario Arts Council had a program for other arts and they were just learning about how to put dance in schools. I went all over Ontario and did that. They funded 15 Dance Lab to produce independent choreographers and then independent choreographers at the provincial and the federal level could apply for A and B grants to do their work and to study. I really wasn’t familiar with BC funding but I’m sure there is a history, we could see it’s development.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. So, that's why you had to start your own company.

Jennifer Mascall: Had to become incorporated.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, okay. Following that, would you be able to describe where you and your community were located at that time in Vancouver?

Jennifer Mascall: Well, I just came to the Western Front. That was it.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, as you said, “the centre of the world.”

Jennifer Mascall: The dance studio was downstairs and The Lux and their work was upstairs in the art gallery, so we weren’t all working together there. Linda Rubin had been a large influence for Peter Bingham, Helen Clarke, Lola Ryan, Katherine Lee. Gisa Cole had a studio, Prism, and every Christmas – I'm not sure of the years – they brought in a Cunningham teacher. It was a way that the community met those who were interested in technique. That and Chiat Goh’s ballet classes were a couple of the gathering places. Then, Simon Fraser [University] had the Phyllis Lamhut composition course, so I did that in June – twice at least, but she had been coming for years. In terms of dance – not for me, but for the people that were here, one of the major catalysts was Iris Garland because she just encouraged anybody to go for it. Go for it and develop your discipline along the way, or just go for it.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: And she was one of the key players up at SFU, right?

Jennifer Mascall: You would have to talk to Santa Aloi and John Macfarlane and Evan Alderson, but my sense is that she started the dance department. At first it [the Dance Department] was a series of projects, like bringing in Phyllis Lamhut out again and again and again. That kind of thing.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Savannah [Walling] was saying that a lot of these workshops were free as well, and that was really important because people had access to these teachers.

Jennifer Mascall: Yes, I get a sense from Savannah [Walling] that the effect of the community made through free SFU workshops was one of the catalysts for starting Terminal City Dance Research, which evolved into The Dance Centre.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Very cool. Going back to SFU again, did you ever do any teaching there, or have any other type of involvement?

Jennifer Mascall: Peter Bingham says yes. Peter hurt his knee and then went and traveled around the world with Helen [Clarke]. When I came back [to Vancouver], he had just come back from his world trip and thought dancing was over. He said that there was something I did, or choreographed that he thought was in connection with Simon Fraser [University] that made him realize he did want to dance after all. I think in the ‘80s and ‘90s, I was occasionally a sessional at Simon Fraser [University]. I think there was a year that Barbara [Bourget] taught one course and I taught another course during the ‘80s, but no, I wasn't really connected with Simon Fraser [University]. Grant [Strate] brought in the choreographic seminar there one year. I went and taught a workshop to the people there, but no, it wasn't wasn't part of my life.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. So, Western Front was your site.

Jennifer Mascall: And we would come to Terminal City [studio] to do some of those improvisation things. I guess that's where we must have rehearsed Chaos.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, it was up there.

Jennifer Mascall: So, compared to that studio, Western Front had a beautiful floor. I think we might have even worn shoes sometimes when we worked it. But the character in that Terminal City studio was incredible, creaky, the balcony, the mah jong parlour below, the many tiny little rooms...

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Someone also mentioned that practices sometimes occurred at Karen [Jamieson's] house, too. That might’ve been just Terminal City Dance though.

Jennifer Mascall: No, I was in a rehearsal in Karen [Jamieson's] living room.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: [laughs] Oh, okay.

Jennifer Mascall: I remember that, but I don't know what it was for. I never minded, it didn't affect the quality of the work

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, the last question in this section: In your opinion, what were the main factors and conditions that allowed the type of work that you were doing at that time to happen?

Jennifer Mascall: The camaraderie of the people that were working here was so great that it was just fun doing things with them. In my mind, I was dreaming to work with dancers that loved contact improvisation that also loved ballet. In 1979, I thought that would make the perfect dancer. And people do that now as a matter of course. But there were so many other incredible elements in people's dancing and thinking that the work was unexpected and we were dazzled again and again.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: And the follow up to that is: How have these factors and conditions changed today?

Jennifer Mascall: I think it's about money. A shift is that we didn't seem to be impeded by a lack of money. Whereas now, money, and how they're going to live, and find a place is first and foremost. It feels like it’s on every dancer's mind.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, it's not so much about funding, as it is about affordability.

Jennifer Mascall: Not funding, just money: How am I going to pay the rent? How am I going to do this? Is working with you going to allow me to pay the rent? That kind of thing. It's just really practical. At that time, those practical things seemed to just fall into place. They weren't like first and foremost in front of us. Peter Bingham says that he remembers a conversation that he thought led to EDAM which was, How are we going to do this? How are we going to make this happen? Which meant, let's start something that would make this happen!

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, a company! [laughs]

Jennifer Mascall: A society. Yeah.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. So, that's the end of the first section here. Now we're moving into the project-specific area of the questions. What is your first memory of Coming Out of Chaos that comes to mind?

Jennifer Mascall: It was what I referenced before: Karen [Jamieson's] phone call while I was in Toronto choreographing Piebald and Duff. Karen [Jamieson] said: Couldn't you change the time to come back? I was in the middle of a creation so the question shocked me. I think of that question as a characteristic of Karen [Jamieson]; she will just go for it, and just say what she wants, and I admire that.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, even though it may not be practical [laughs].

Jennifer Mascall: It was completely impractical! [laughs] Lola Ryan remembered Savannah Walling gave us warm-ups, but I don't remember that at all. I remember a scenario: Karen [Jamieson] was asking Lola Ryan, Peter Bingham, and myself to do something... I know where I was in space, and I can see Karen [Jamieson], and I knew by the words she was using, she just wanted some sort of fabulous, great buoyant moves, and Peter [Bingham] and Lola [Ryan] asked her, What should we do? So, she gave them some moves, and then she asked us to do it, and Peter [Bingham] and Lola [Ryan] turned to me and said, in outraged tones:You were improvising! You weren't doing the choreography! And I laughed and laughed and laughed and laughed because what was in the room were people that had lived improvisation, and that's all they’d done, and choreography was something else. So, we're going to do choreography now. It was like that. It's probably threaded throughout the rehearsal period: What was improvised and what was choreographed? And what is choreography? That kind of thing. I think that's probably the moment that led me to think that choreography is the boundary within which you improvise. So, the boundary there was just the phrase, and she'd [Karen Jamieson] liked some shapes, but really I could see the longer thing of what she wanted. I don't know what it was, but just this thread of people coming from different points of view, and how they would look at an instruction, and how they would interpret it [was] just really, really fascinating.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, all the different vocabularies and understandings.

Jennifer Mascall: Just completely different understandings.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: It's interesting because that kind of goes right back to what you've stated from the beginning, of just being interested in how other people think, and how they make [decisions]. That encapsulates the moment in a way: working with this handful of people who have really different backgrounds and interests and ways of thinking – and that sometimes manifests into a state of chaos because those understandings don’t always work together or match up. I guess that created a frenetic environment at that time.

Jennifer Mascall: I have no memory of any of that. Being frenetic, or chaotic, or anything. We were just learning a piece. She [Karen Jamieson] was trying to make a piece and we were just trying to help her out. However, we were all mature. We weren't beginners. We were all not young, so there were lots of conversations throughout.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. So, my next question is: What was your impression when you were approached by Karen [Jamieson and Grant Strate] about participating in Coming Out of Chaos? So, that would have been the phone call.

Jennifer Mascall: I had no recollection of Grant [Strate] being part of it, or Grant [Strate] commissioning it, or anything like that.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: He was the one who encouraged Karen to do this piece and then helped her get the funding for it as well. I wasn't sure how involved he was, whether they both approached the participants or if it was just Karen [Jamieson]?

Jennifer Mascall: In my case, it was just Karen [Jamieson], and what an amazing impresario Grant [Strate] has been for forming the choreographic life in Toronto, and in Vancouver, and in Canada.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Truly. So, maybe the question we focus on here is why did you participate?

Jennifer Mascall: Oh, it's so much fun to be a dancer in somebody else's process. It's like going on holiday because you don't have to find the grant. They've got the grant. All you have to do is just help them out. So, there was not a second of hesitation.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. And when you weren't able to make the first few rehearsals, did you reach out to Barbara [Bourget]?

Jennifer Mascall: No, I didn't. I didn't do anything. I just went back to choreographing in Toronto [both laugh]. I don't know what happened.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Do you remember when you got back and started the rehearsals, did you ever have to meet up with Barbara [Bourget] to review the choreography?

Jennifer Mascall: No, I'm sorry. I don't remember that at all! [laughs]

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: That's okay! Just wondering.

Jennifer Mascall: I'm interested in why wasn't Barbara [Bourget] in it also.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: She left. That was her choice.

Jennifer Mascall: Oh I see.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, she had a child at that time, and she had to prioritize putting food on the table. It wasn't the right [financial] situation for her to be able to participate in the project at that time. That's why she backed out. So, what was the most challenging part about developing this piece?

Jennifer Mascall: I don't remember anything being challenging.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: [laughs] What about the most meaningful? Was there anything that came out of it that made an impression on you?

Jennifer Mascall: No, I think it strengthened the collegiality and friendship between Karen [Jamieson] and I which has continued ever since.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, there's definitely a lot of trust-building that goes into that process of working with people. Actually, that's something I was wondering about: the way that the project was explained to you. Was Karen [Jamieson] supposed to be the only one choreographing it? I get the sense that you all ended up being co-choreographers, as well as dancers. How was it framed? The Coming Out of Chaos program suggests that you all had a choreographic stake in the project as well.

Jennifer Mascall: I think that's a polite way of saying that. She [Karen Jamieson] would say we need something: You two go off and work in the corner on that and come bring it back. Something like that, and she would look at it. I think it comes from not everybody having the same vocabulary. They may have the same vocabulary, but may not have done the same training.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, so is the idea of authorship much more fluid now today? People recognize the inherent collaborative nature of these kinds of processes?

Jennifer Mascall: I think that would be an interesting question to investigate. I would say at that time, the authorship was completely fluid, and I certainly knew it was Karen [Jamieson's] work. It was definitely spearheaded, shaped, and moved on by Karen [Jamieson], though some of the moves came through something else because naturally, some of us wouldn't be able to do a move that Karen [Jamieson] could do, so she'd have to make another one or say, Why don't you make something like this or something like that? I would say now, people might question authorship whereas then, no. We were just making a piece, doing whatever we could to make it good.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Right. I'm just thinking about how there was such a focus on having a brand, or a school at that time in Vancouver, right before Coming Out of Chaos. Like, the Paula Ross and the Anna Wyman schools in particular, having a very branded technique, as well as name-branding. This was a moment when the independent choreographer was rising, and these independent, collaborative projects which came shortly afterwards seem to push back at that tradition.

Jennifer Mascall: Huh. Interesting. I don't know. What year was it again? We're talking about '81, ‘82?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah.

Jennifer Mascall: I suspect it wasn't really pushing at that, it was simply working with the people that were there. This is what they can do.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, again, much more organic than intentional.

Jennifer Mascall: Yeah. There's no point [laughs] to stick their leg out if they've never trained in that form, so there's a freedom in that.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. So, my next question is: What did you take from working on Coming Out of Chaos that has shaped or influenced your practice today, if anything?

Jennifer Mascall: I think I said that the friendship and collegiality with Karen [Jamieson] has persevered. It's great to go off and do your own thing, and you're in your own world, and then suddenly, you remember, or you can call, and you can say, Yes, you're doing the same thing over there in your tower, or cupboard, or living room.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, so that type of connection is important for building healthy, creative communities. Do you remember anything about the rehearsals or performances of Coming Out of Chaos, or any impressions or personal feelings about the process?

Jennifer Mascall: I remember that Susan Berganzi's costumes caused a bit of a rumple. Some people liked their costumes, some people didn't like their costumes. That kind of thing.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: They were pretty experimental costumes, weren't they? Did yours have bells on it?

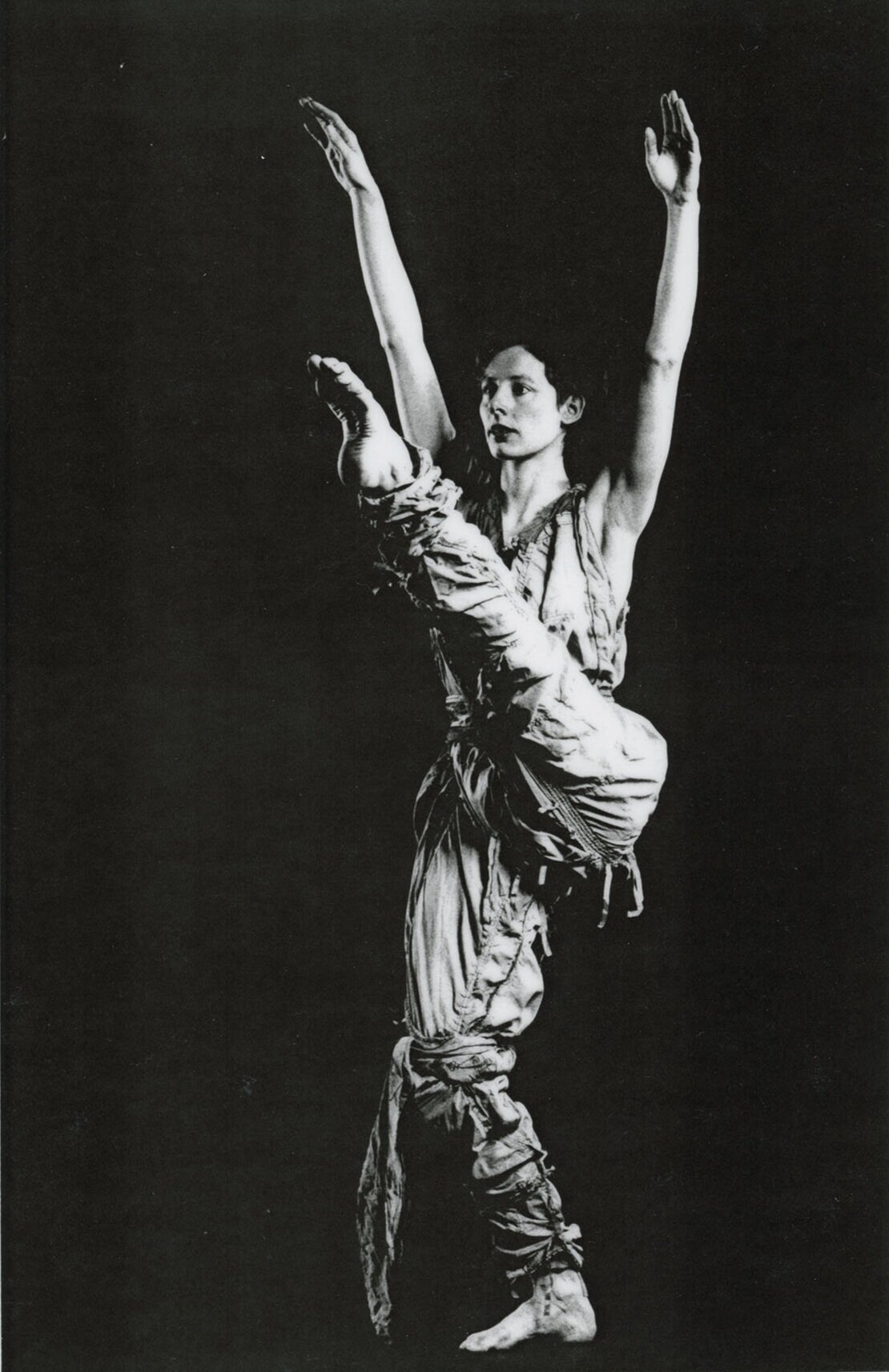

Jennifer Mascall: No, mine had holes in it. Susan [Berganzi] is a remarkable artist, so she brings her art and she does it with the fabric. It brought energy to the piece because she came as an artist, with her own point of view. Her costumes caused excitement.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Did you like your costume?

Jennifer Mascall: It was just fine. I thought I liked it very much. I remember falling through one of the holes in the costume on one of the moves that I did. I remember one performance falling on the small ladder that Karen was standing on in a hot studio that had pillars. That's all I remember.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Do you remember any interactions with the other dancers?

Jennifer Mascall: I remember no interactions with any of the dancers. I have three memories from the piece: The falling (I mentioned); doing a front developpé in Montréal; and watching Savannah [Walling] and someone else do a characteristic trident move of Karen’s.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: People have pretty strong memories of improvisation sessions with Ahmed [Hassan], in terms of playing around with –

Jennifer Mascall: –his music.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yes.

Jennifer Mascall: No, I remember making something for us to eat on tour. I made some Nanaimo Bars and brought them because I'd never heard of them before I got to the West Coast. The irony is that just last year on CBC, I heard that Karen [Jamieson's] husband at the time, David Rimmer, his mother invented Nanaimo Bars, but I didn't know it at the time, and nobody mentioned it over these subsequent decades.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: That's hilarious. Do you remember anything about the first performance at the Waterfront Theatre on Granville Island?

Jennifer Mascall: No, I don't. I remember Open Space in Victoria.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Do you remember seeing Karen [Jamieson’s] Solo From Chaos? It premiered at the Dance Conference in Ottawa shortly after in’82.

Jennifer Mascall: Yeah, I saw it there. It made a wonderful solo. Ahmed [Hassan] was fantastic and Karen [Jamieson] was fantastic.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Is there a single word that you would use to describe the process of developing Coming Out of Chaos?

Jennifer Mascall: Luxurious.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Peter [Bingham] also said something similar. He mentioned that there was some form of payment for attending rehearsals which was a big thing at the time. Even though it was for a short amount of time, seeing some money come in from that work was “luxurious.” Other people have described it as chaotic [laughs].

Jennifer Mascall: I have no memory of it being chaotic. It was fun. You'd go and hang out with these people and you'd do what you could because it was Karen [Jamieson's] piece. She was gonna take care of us. We just had to be good [laughs]. There was no pressure anywhere.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. I think Lola Ryan and Peter Bingham also articulated that they found it challenging at times to understand what exactly Karen [Jamieson] wanted, like the way that she was articulating what she wanted them to do was not always clear to them.

Jennifer Mascall: Yeah, they weren't familiar with a traditional ease of working in a dance studio.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: As in they come from different backgrounds, different vocabularies, as we've talked about? [Jennifer Mascall nods head]. Yeah. Okay. Could you share some memories about working with Ahmed Hassan, Lola MacLaughlin, and Elyra Campbell, if any?

Jennifer Mascall: On that project?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: I would say start with that project if there's anything you can remember, and if not, then any other projects. I just want to get a sense of what it was like to work with them because I'm obviously and unfortunately not able to speak with them.

Jennifer Mascall: So, I don't remember them at all in the project, but I worked with Lola [MacLaughlin] for seven years at EDAM, and we had worked together two or three years before EDAM. She had a very sophisticated aesthetic sense.

I have a good story about Ahmed [Hassan]. We were on tour in Newfoundland with EDAM and he said he'd like to do a solo, and he'd never done a solo, and he wanted to do it with his berimbau. So I, who did solo performances a lot, said, I'll work with you. So, I worked with him, and in my arrogance, I thought I was great. I showed him different parts of the stage, and what that felt like, and where that was, and just stuff. Then, that night when he was going to do the solo, he came out up-stage left and took two steps, and one step had one leg down and the other step, put his foot directly in front with his feet going in the same direction. And he turned his head, with his berimbau, and that's where he stayed, like a frieze. He didn't follow any of my instructions. And I looked at him, and I thought, What is he doing? How can he do that? And then I realized, Yes! You're Egyptian and you're standing like an Egyptian! It was amazing. It was like just him going to the essence of what it's like to do your first solo – you just go, you hunker down! So, he had just gone to his essence and done what he knew. It was remarkable.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Oh, that's so good! [laughing] You must have been shocked.

Jennifer Mascall: It was really brilliant and revelatory. How patronizing to think I could teach him about how to do a solo.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: And did you know Elyra Campbell through anything else? [Jennifer Mascall shakes her head]. No. Okay, didn't know the name? Savannah knew her. They were relatively close friends. She's also passed away sadly.

Jennifer Mascall: Lola [MacLaughlin] and Ahmed [Hassan] lived on the corner of Columbia and Hastings Street. She and I connected because we both practiced zazen, and so I would often go there and we'd sit zazen together. Then later, we both became interested in the Russian Orthodox Church and I joined it a couple of years before Lola [MacLaughlin], and became her Godmother in it.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Interesting and Lola [MacLaughlin], was she from Toronto as well?

Jennifer Mascall: No, she was from Osoyoos.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Oh, she's from Osoyoos! And Ahmed [Hassan], he moved to Toronto shortly after Coming Out of Chaos – No! EDAM. He was with EDAM for a while, and then after that moved to Toronto.

Jennifer Mascall: Yeah. And worked with Desrosiers [Dance Theatre].

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Did you continue a relationship with Ahmed [Hassan] after he moved away?

Jennifer Mascall: [nods head] He was friends with everybody.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, I get that sense [laughs]. And then did Lola [MacLaughlin] also move to Toronto at some point?

Jennifer Mascall: She danced with Desroisiers for a bit as well. And worked with Claudia Moore.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, we talked about this a little bit already, but do you feel like Coming Out of Chaos played an important role in starting EDAM?

Jennifer Mascall: Oh, not at all.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: You were recollecting earlier a conversation that you had with Peter [Bingham] about the beginnings of EDAM. I think it's in his autobiography too.

Jennifer Mascall: I see. That is what Peter Bingham remembers. There will be at least seven memories of how we started. What I remember is being in a car with Lola Ryan. Lola and I connected because she was interested in dance history because she was a dance critic. So, we talked and talked and talked about dance and dances we'd seen and things like this, and what I remember is one of the conversations in a car with Lola Ryan, saying, Gotta do something here. Why don't we start a collective? And then Peter Bingham remembers, later on, Ryan and I talking about how we're gonna make our living. So, the first person was Lola Ryan, and then we must've asked Peter Bingham. I asked Lola [MacLaughlin] in 1980, after Brain Drain, and then Ahmed [Hassan] was part of us all, and then Barbara [Bourget] and Jay [Hirabayashi] because of Paula Ross and the ballet connection, we felt like they'd be a good balance. Jay [Hirabayashi] wasn't really interested because he'd been part of a cooperative daycare and it didn't quite work out, but I convinced him.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Nice. Okay, and then how long were you involved with EDAM for?

Jennifer Mascall: ‘Till 1989.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: '89. Right, when you incorporated. And then at that point, Peter Bingham became the sole Creative Director?

Jennifer Mascall: Yeah.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Do you think a work like Coming Out of Chaos would be made today? Why or why not?

Jennifer Mascall: Please describe what you think the dance was like?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: From what I’ve read, it seems like it was considered a pretty groundbreaking piece at that time; the way that it was made, bringing together these people in this way. Is that different from what happens today, or not particularly?

Jennifer Mascall: I think it's of a moment. So, for example, I think having people that do their own work, have their own companies coming into a work room together is exciting because the imprint of our thoughts are carried in the way we move. I think the nature of project work is that people are intermingling. As I've mentioned earlier, it is a holiday to dance with somebody else. It's the way to keep things healthy and to keep things friendly and it’s really great to be in a room with another choreographer and to see what they think.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, and to see how they're approaching it differently. After reading the newspaper articles and reviews, it seems like it was really well-received. Audiences really liked Coming Out of Chaos. I guess I was also wondering, focusing more on dance criticism and writing for a sec, how do you think it would be received today by critics? I don't know if you're involved in writing or dance criticism these days...

Jennifer Mascall: No, I'm not involved in that. But not that many people are writing now about dance – like writing reviews or criticism, that kind of thing. People are writing about the ideas caused by a particular piece. So, is the underlying thing that you're asking: Is the piece dated?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Or how does it hold up over time?

Jennifer Mascall: Because I can't remember any of it, I really can't say, but I saw what Karen [Jamieson] did with the Solo, where she had three people [Josh Martin, Amber Funk Barton, and Darcy McMurray] do the Solo [recently], and that seemed to be really interesting – especially the fact that the dancers were doing Ahmed [Hassan's] voice on the [microphone]. (2) I'm very interested in that.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Totally, yeah. I saw that piece as well, and I thought it was amazing. Just getting to see the play between the music and the dance. Generating sounds through the body.

Jennifer Mascall: [We’re doing a] Lurch project over the next two years. It's like a legacy project where we're taking a sculpture from a dance done in two seasons and a tour in 2010, ‘11, '12. And then I've commissioned three other choreographers and I'll do it myself in the same cast; four women and a cast of five men, and we're working in workshops where they address how they look at this object – which is a huge object, and how they would make a piece with it because the way women approach objects is really different than the way men do.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: And it’s a pretty daunting sculpture as well, right? Designed by Alan Storey?

Jennifer Mascall: Well, it is. We did our first one this summer, and yes, it looked daunting at the beginning, but then it wasn't daunting at all.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: [laughs]

Jennifer Mascall: Once we started to work on it, it was really, really, really interesting. So, for me, one of the ways to look at legacy and archive is to open up the conversation.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, this is a piece from the past and you're redoing it with these new dancers?

Jennifer Mascall: No. I have given them one third of the sculpture that we used to make the original piece. They're just addressing whatever they want with it. But of course, one of the dancers in it was in The White Spider, so they bring that history, and yeah, by being in the room, I bring that history. It's interesting.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Very cool.

Jennifer Mascall: It’s a great way to think of archiving.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Kind of similar impulses to Karen's Body to Body project, but I like the idea of just bringing in one element of the past. Last question here: What kinds of stories do you want to hear and in your opinion, need to be told?

(2) See Body to Body: https://www.kjdance.ca/now/b2b-2018

Jennifer Mascall: I don't know. A good story is a good story. I love hearing a good story. So, it would be great to get some things that are not politically correct [laughs], but unfortunately I can't think of anything not politically correct to do with Coming Out of Chaos [laughs].

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Well, as I said, it's a launching point to go off of. Working for Karen Jamieson, it’s an important work for her as she went on to establish her company, but the project idea was to have all of these other perspectives brought together too.

Jennifer Mascall: I think it's very gracious, and because you're writing the history, it's really important the history not be from one point of view.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, we’re going for multiplicity.

Jennifer Mascall: All right. Thank you.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yes. Thank you!