“My history resides there on that floor.”

Lola Ryan & Emma Metcalfe Hurst

Interview for Coming Out of Chaos: A Vancouver Dance Story

July 23, 2019

Lola Ryan, Teacher, writer, performer, and dancer in Coming Out of Chaos (1982)

Emma Metcalfe Hurst, Karen Jamieson Dance Archivist/Creative Director of Coming Out of Chaos

This oral history interview has been edited for length, clarity, and accuracy

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: What is your background entering into contemporary dance? Can you please share your dancing story.

Lola Ryan: Well, I'm going to go start with growing up in Ontario. I always loved dancing and when I danced, everybody would move away from me on the floor because I took up a lot of space. I had a girlfriend at university who was in the Dance Club at Western University, which was part of Phys Ed so it wasn't actually dance, but her teacher was a former [Alwin] Nikolais dancer, which was kind of cool. I used to go out with them on Thursday nights after their rehearsals and we'd dance together and she said "Well anytime you want to join the company, you're welcome." But I didn't. Growing up in Ontario at the time in the context of dance, it was just not part of the culture that I was living in, so I didn't even consider it really until I moved to Vancouver in '74. I had a teaching job, work equivalent full-time permanent position teaching English which was quite unusual at the time. And by January of that year I just thought, “What the hell am I doing? I'm spending my nights at home like I'm still a kid.” I thought, “No, I have to dance.” So, I asked around and I found Linda Rubin and Synergy. So, it was January of '75 that I first stepped onto a dance floor, which of course, that was the studio that became the EDAM studio [at Western Front]. So, it was a long, long relationship to that floor, and EDAM. So as you probably know about Linda, she taught Graham technique and some ballet and then the basic expression–form of expression, was improvisation. And she was the one who brought John Gamble in from California to teach us contact. The first person we had had only done one workshop and then he was teaching. It was crazy. Anyway, by half-way through the year, I had decided to quit teaching and become a dancer. Linda had invited me into her company in that same year that I started so I was pretty excited. And it was Vancouver in the ‘70s. At the time I was a man. There was money around, there was opportunity. So, no one worried about stability or security. You just did what you needed to do, and so that's where we began. And very soon after we started bringing in people like Steve Paxton and the Improvisational group Reunion and there was me and Andrew Harwood and a bunch of us who all got together and we were the improvisers doing small improv in informal performances, so to speak. We called ourselves Around Nine, and very soon after that we began to move away from Synergy with Linda and went out on our own. So, that was the sort of hotbed of what I was doing. We were bringing in people to study with. I went to Vermont to study with Steve Paxton and basically the cream of the New York Postmodern scene, and met all these wonderful people and subsequently was asked by Steve [Paxton] to go down to Provincetown to perform with them. So, that was pretty interesting because it was only two years after I had started dancing. I was performing with [Steve] Paxton and it was a wonderful beginning. And then coming back to Vancouver, we just kept on going. I started teaching at Langara College and we were teaching at the Western Front, Peter Bingham and myself especially, and creating small sorts of impromptu performances so to speak. And that's how it was for that first four or five years at the time. And I'm not sure if I had taught Karen [Jamieson]'s company before Coming Out of Chaos or after, but she invited me in and I taught a series of contact classes for them. And, surprisingly, when I saw their performance, she used every single exercise that I had taught. I thought, “That's interesting.” I only thought of them as exercises but of course, Karen [Jamieson] being more of a choreographic mind, saw them as resource material, as tools to actually put into the piece. That was an awakening for me. So, that's where I started basically: with a very strong background in improvisation and contact improvisation. This all follows from my athletic background. I spent 10 years in rowing, I was on the National Team. I was highly physical and then a long distance runner after that and then it all segued into dance where I put it all together, which was a wonderful opportunity.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Amazing. When did you do a workshop with Steve Paxton?

Lola Ryan: We brought him into Vancouver to teach before that. I believe in 1976, the whole bunch of us: Peter Bingham, Helen Clarke, Andrew Harwood, Seamus Linehan, we all went down to California. First, we went to the Naropa Institute [in Colorado]. This was the summer of 1976, right after I quit high school teaching, and we studied with Nancy Stark Smith, and a few other people. And then in August/September of that year, we all convened in Berkeley to do something – I forget the name of it now, but it was a month-long, intensive contact and related disciplines that we all went to. The group behind the intensive was Mangrove, an all-male dance group. So, there was a group of ten of us from Vancouver (we were called "The Vancouver Group”) coming down there and that was really quite exciting. The next year, I was the only one who went to Vermont and met the East Coast version of contact and improvisation which was wonderful. Very different than the West Coast. The West Coast was very experiential and emotional. The East Coast was more... they sat around, they talked about what they did. They talked about concepts and techniques, and not quite formal, but more studied because these we’re people who came out of the Postmodern movement in New York. When I came back to Vancouver, I brought that with me as well. So, there was an interesting combination of Eastern, and Eastern US, and then the Western US influences that we merged in Vancouver in the scene that we created.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Interesting. So, would you be able to describe the creative atmosphere of that time? There seemed to be a very strong sense of community and collaboration as well.

Lola Ryan: It was very loose I would say, more than anything else. We just floated from project to project. We had, like I said, a very informal group of people who danced together. Gillian Lowndes was one of them, who died shortly, a few years later. She was the first one we lost. Other people were there initially, but it was Peter Bingham and Andrew Harwood and myself who really stayed with them. Andrew left shortly thereafter to go back to Eastern Canada and then to Europe. He wasn't in Vancouver for all that long before he took off on his own career. But Bingham and I stayed. Linda Rubin was still chugging along with Synergy and producing dancers. It was a very, very fertile time for things going on. You could teach here, you could teach there. Peter and I taught a lot together. We performed together. We went to Victoria and performed and taught together. So, there was a lot of cross-fertilization going on. And then of course, Lola MacLaughlin, Ahmed Hassan, Jay Hirabayashi, Barbara Bourget, and Jennifer Mascall were people who we met as we developed. We met them basically because of contact improvisation and the work that we had to share with the community.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Right, right. Were there common interests and themes that you were all addressing collectively, either consciously or maybe looking back in retrospect? I’m curious if this type of dance spoke to certain contemporary issues and events, such as the civil rights movement or anti-institutional sentiments?

Lola Ryan: I can't speak for everyone. We didn't necessarily sit around and talk about the context of contact but I have to say that it was the sort of organizing principal symbol for the dance that I did. Because I was still very involved in athletics and running and sports, I went through a book called The Ultimate Athlete by George Leonard. And a very prescient statement he made was this: "I'm not sure that a dancer is the ultimate athlete, but I am sure that the ultimate athlete is a dancer." And so I was very much involved in studying the body, anatomy, experiential anatomy and also Zen poetry. Gary Snyder and the Beat Poets and that whole scene informed what I would do because of course, I came from a literary background as well. So, I always put this into a context wider than just the body. It was Snyder's writing about Eastern mythology, and Eastern wisdom that was an underpinning Contact for many people. Steve [Paxton] himself had studied Aikido, had lived in Japan, and studied meditation. So contact was an alternative to simply going into the studio, learning the technique, making a dance, and performing it. It was more of, dare I say, a lifestyle, though I can't really say how I lived that way. Contact involves flow and cooperation between people, lack of controlling of others, listening, partnering, supporting. So those were all the things that Peter and I very much were immersed in, in those years and I think it informed a lot of what we did. Peter [Bingham] was involved with Helen Clarke at that time, she was one of the initial group, [Fulcrum]. She's in Australia now but she too was very much like me, interested in poetry and writing and the creative aspect of things. Contact and our work just flowed organically into that. What I said back then was: "Dance is an ideal combination of mind muscle," so it wasn't just a kinetic thing, an unconscious thing, you actually could be very consciously doing things, consciously understanding how your body worked, how it worked in relation to others. Basically, how you should live. It sounds so organic and holistic, doesn't it? [laughs]

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: It does have a certain kind of idealism or utopian aspect to it in some ways. By the time you got to Coming Out of Chaos, it seems like you'd all had a lot of experience by that point and were ready to go on and establish your own trajectory or voice within the dance world.

Lola Ryan: Yeah, yeah, it was starting. My very first solo was 45 minutes long. It was called Between Shores and it was me, and the texts, my favorite texts from T.S. Eliot, from Gary Snyder, from John E. Muir, the American naturalist, Charles Olsen. And it was a way in which I integrated all of the things that I was interested in and put it into a piece. I actually climbed the floor as if it was a vertical rock face.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Oh wow.

Lola Ryan: And I can't do that anymore. I don't have the strength, but I did. And it was a wonderful piece and it was again, a combination of East and West which I think contact is– it's a Western creation, but it's full of Eastern influences.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, you've touched on this a little but I was wondering if you could talk more about where you were drawing your personal influences from? You’ve talked about Eastern and Western influences. How would you go about describing the differences between Eastern and Western contact?

Lola Ryan: In terms of contact improvisation, it connects to a lot of World Dance, World Folk Dance. The emphasis is on grounding rather than flying. In ballet, in many instances the torso is pulled up, the energy is coming higher up into the body. Whereas in contact, it drops down low into the centre, and into the ground. It's a much more grounded kind of form than say balletic, which doesn't seek to deny gravity but gravity is not the element. In contact, however, we embrace that. So, it’s a very different way of thinking about how you navigate through the world. If you think about flying or rather grounding, if that makes sense?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Definitely. I'm also wondering what were some other driving forces that we’re influencing dance production at the time? I'm thinking about funding – Pierre Trudeau coming into power and increasing funds for Canada Council for the Arts and how that affected the dance community at that time.

Lola Ryan: At that point in 1979, 1980, I was trying to get funding from the Council for contact work and the officer at the time refused to accept it as a valid art form. And I said, “Well, Steve Paxton is an amazing Cunningham dancer.” He said, "Well, Steve has, let's face it, modern dance, credentials." So, the rest of us bumpkins, contact people, you know, scruffy and coming from left field, we didn't qualify. So, we weren't really able to get funding at that point. It was only when EDAM formed and then we had people like Jennifer [Mascall] and Barbara [Bourget] and Lola [MacLaughlin] who were in the modern dance world that gave us some cachet. But as for the improvisational aspect, we were still sort of on the fringes of things at the time, improvisation as a means of performance rather than just something to do, you know, just self-expression. We performed using it, and that was a different thing. At that time, I was reading furiously. I was reading all the dance history I could find. I actually did get a Canada Council grant and spent three months in New York studying. That came a little later in my evolution, after Coming Out of Chaos. But my interest was always contact, also within the context of dance itself, like dance history: who had done what, where, when, why, and how, and how do we fit into that? So, that's part of my academic orientation to a lot of this. I spent all that time in university and I never wanted to leave it behind.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: It seems like that's something a lot of dancers struggled with at that time, having to continue with their engagement, their passion for dance, but then also having to contend with reality, and responsibility, and adulthood and all these things. That was something that Barbara [Bourget] mentioned about having the responsibility of a child at that time and having to take different jobs here and there just to scrape by, or having these moments where you take a break from dance, but eventually get called back into it.

Lola Ryan: Well, to be honest Emma, at the time, it was easy for me. There was always work. There were always things to do. I always had enough money. I used to tutor dyslexics on the side. I would get money for that and then I would go away and study in the summer, or whenever it was, and I ended up going to Europe to study. I studied, as I said, in Vermont with [Steve] Paxton, but I went to France and worked with Monika Pagneux, who used to work with Peter Brook Company, and with Ludwig Flaszen, who was the co-founder of the Polish Theatre Lab with Jerzy Grotowski. So, a lot of my experience was based on European traditions of training and improvisation. It wasn't what was being offered in Canada and the States necessarily. I worked with Yoshi Oïda too, the Japanese dancer from Peter Brook's company. That, again, was the combination of East and West that I was immersed in, and blessed actually to be able to participate in those things at that time. I had enough money to do it. I wasn't struggling in a sense. I didn't have a relationship, I didn't have children at that point, so I was a pretty free spirit.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. You can move around a bit easier that way.

Lola Ryan: Yes. I wouldn't say that Peter [Bingham] was any different too. He and I were kind of on parallel paths in that respect. We floated very, very well and easily at that time.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: I read somewhere that you also have a theatre background?

Lola Ryan: I have no formal dance training and I have no formal theatre training. However, I've taught at the National Theatre School, I'm teaching at the University of Ottawa, I taught at Simon Fraser. Basically, I'm self-taught, but I did what used to be called the “guild system.” When I needed something, I found a teacher and went and studied with them. I didn't enroll in a school. With the exception of York University and Simon Fraser dance departments, there wasn't much dance training in Canada, but it was starting. But I never did any of that. I was already too old. I didn't start dancing until I was 28.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Wow. Yeah. That’s late!

Lola Ryan: I just skipped all that. I had all my athletic training but not formal dance training.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: There is definitely something to say about just throwing yourself into it–learning through an embodied experience, as opposed to over-conceptualizing it too much, or going down these traditional, formal training trajectories. The self-taught methods and collective opportunities to learn from each other seem like one of the unique features of contact in Vancouver?

Lola Ryan: Well, it is. I’ll say this for me – and I can't speak for others because I was working very differently. I was studying composition on my own and studying it via visual art and music and poetry because, of course, when you get down to the basic forms, there is a lot of similarity. And so, if you look at music, you understand something about rhythm, timing, balance, support, leads, solos, and the same in visual art. How do you look at a painting? So many things like that informed how I was working, and I was doing this by myself. There was no one else. Just me and my books and my mind and my journals. So, I worked very hard at educating myself beyond just doing the contact itself.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, yeah. I was actually really drawn to your background and how you came to dance. You speak to approaching it from visual arts and also your athleticism. That's a really interesting perspective. I also think the interdisciplinary, or multidisciplinary, quality of this dance community also seems unique to Vancouver at that time.

Lola Ryan: In terms of the cast of Coming Out of Chaos, Jennifer [Mascall] came out of the York [University] program, and of course, Grant Strate had been there when she was there. She came through in the Golden Years. I mean, all the TDT [Toronto Dance Theatre] people were training at York at the same time. Susan McKenzie was there, Terrill Maguire, the two women part of Toronto Dance Theatre, Pat Fraser... They were all at York. And so Jennifer [Mascall] brought formal training to her work, but of course, she was a renegade from the beginning.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: The next question I wanted to ask you is where were you and your community located? What spaces and neighborhoods did you work out of?

Lola Ryan: Essentially the Western Front was home, initially because Linda Rubin had that place as her Synergy studio, but then she outgrew it. I think you can basically say that. After that, we went over to what was the [Arcadian Hall, later known as the Main Dance Place run by Gisa Cole]–which now, I think, has burned down–on Main Street. But that left the Western Front, and Jane Ellison, who was part of our group as well. So, we basically took over the Western Front studio and ran our classes and did all our teaching and performing there in addition to being at the Main Dance place, in the studio that Linda set up there, the Synergy studio. But eventually, we all became more associated with the Western Front. I was teaching at Langara too, and I organized my own dance tour through the interior of BC one year, for a month, and went around, taught, and performed, but always came back to the Western Front. The other thing was that Steve Paxton had a connection to some of the artists at the Western Front as well. So, when he came to Vancouver, he would stay at the Western Front. Our associations with Steve, who was very much respected by the artists at the Western Front, meant that they looked favorably on us because we weren't just modern dancers. We were doing different things, like [Peter] Bingham and I dancing on broken glass and things like that. Climbing and descending stairs while dancing, which we did. Do you know about that piece?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: I don't know about that piece, but it reminds me of the performance artist Chris Burden who did a piece with broken glass.

Lola Ryan: Well, we danced in a box full of broken glass.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Oh my gosh.

Lola Ryan: And then we danced in a square that was suspended and floating–a wooden square that had glass bottles, broken bottles, glued to it, and we danced inside it, doing a full contact dance together, Bingham and me. That piece was called Laughter is a Serious Affair.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: [laughs]

Lola Ryan: It was my idea, but it took me three days to convince [Peter] Bingham to do it. But there was another aspect to it too because, again, because of my background, I called it a three-part duet about free will and determinism and it was a debate. We had a debate while sitting on a chair, or a couch, moving all over this place–again, at the Western Front. And deciding: “Well, is this movement something that is determined? Or did I decide to do this?” And so, Bingham and I got into a heated argument, in performance, about whether dance is an example of free will or determinism. The philosophers had a field day.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah I bet. I guess these are the types of questions that contact improv brings up?

Lola Ryan: Well, they're my questions. They weren't necessarily contact, but they were the way my mind was thinking. And so I brought that back into contact, like, what is contact? Where does it go?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Where does it come from? Yeah. I was wondering if you could share any vivid descriptions of the neighborhoods or some of the studios you worked in. Maybe the Western Front studio?

Lola Ryan: You know, the Western Front studio basically now looks like it did when I first went there. It hasn't really changed. Peter [Bingham] has opened it up, but essentially, it's as it was, so my history resides there on that floor. I wish I could see my footprints on the floor, but they're not there. So, that was my real home, to be honest. I had a studio when I taught at Langara, when I taught theatre students. That was a space that I used a lot. And Steve [Paxton] came up and watched my classes there too, which led to other work where I was blending contact and Shakespeare which was really interesting. That led to me going to Greece seven times to teach a dance company, courtesy of Steve [Paxton]. And basically, what I did there was I taught contact but we also did Antigone, duets from Antigone, using contact improvisation as the movement base–Antigone and her sister were having an argument.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Wow, I would have loved to see that.

Lola Ryan: Again, that's where my mind goes: combining text and idea and thought and image with the flow of contact improvisation, but making sure that the text did not follow the dance. And the dance did not have to illustrate the text. They were parallel structures. And it was up to the audience to see the connection, which they did. That work was in the ‘90s, so this was after Coming Out of Chaos.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Mid-’90s or so?

Lola Ryan: Mid-’90s.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Okay. That’s good to know. I think you've mentioned it in passing briefly earlier on, but what was your involvement with The Centre at SFU if any?

Lola Ryan: I applied to teach there, and I think it was Santa Aloi who was there at the time–no, it was Iris Garland. I taught a series of contact classes. I wasn't involved in performances or any other aspect of the running of The Centre. I did interview Grant [Strate], but other than that it was just a place, another venue to teach.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, every dancer in Vancouver seems to have a connection to SFU.

Lola Ryan: Yeah. Lola [MacLaughlin] had studied and taught there, but I didn't meet Lola at SFU as far as I can remember. I went in and taught young dance students. Tom Stroud was there, Darcy Callison... a lot of people who went on and did other things, but basically I was there to teach them some contact improvisation because they realized it was a necessary part of dance training, as it is today. It's now taught at the National Ballet School too.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Wow, that’s great. So, what were the main factors and conditions that you think allowed this type of work to happen? And how do you think some of these factors or conditions have changed today?

Lola Ryan: Well, it was the ‘70s. It was Vancouver, “Lotus Land.” There was money around. There were jobs, you could get a job really easily to support your dancing. It was cheap to live, believe it or not. It was cheap to live there. And so, it was a very laid back laissez-faire kind of environment that I moved in. And I think basically that's how many people felt about Vancouver. If we wanted to do a performance, we just did. We didn't have to ask anybody's opinion. We would get our letraset out, we'd make our little posters, we put them up and people would come. It was easy. Now, if I had been perhaps, like maybe some of the other members– more formally looking to be a choreographer, and to have a company, and to rehearse with them, and with all the accoutrements of conventional performance, it would have been a different story, but we didn't think about sets, costumes, or props or anything like that. Lighting and sound were the only things that we concerned ourselves with and they were pretty rudimentary to be honest.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: And then I guess you were also starting to get the equipment to start recording your performances and rehearsals as well.

Lola Ryan: Yes, but as you know, thinking about documenting and recording the work was the very last thing we thought about. Even at EDAM. We didn't care about posterity or legacy or a solid body of work. At least I didn't. Possibly others did, but I can only speak for myself. I wasn't looking at it in those terms at all.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So, moving on to the next section of questions, what is your first memory of Coming Out of Chaos that comes to mind?

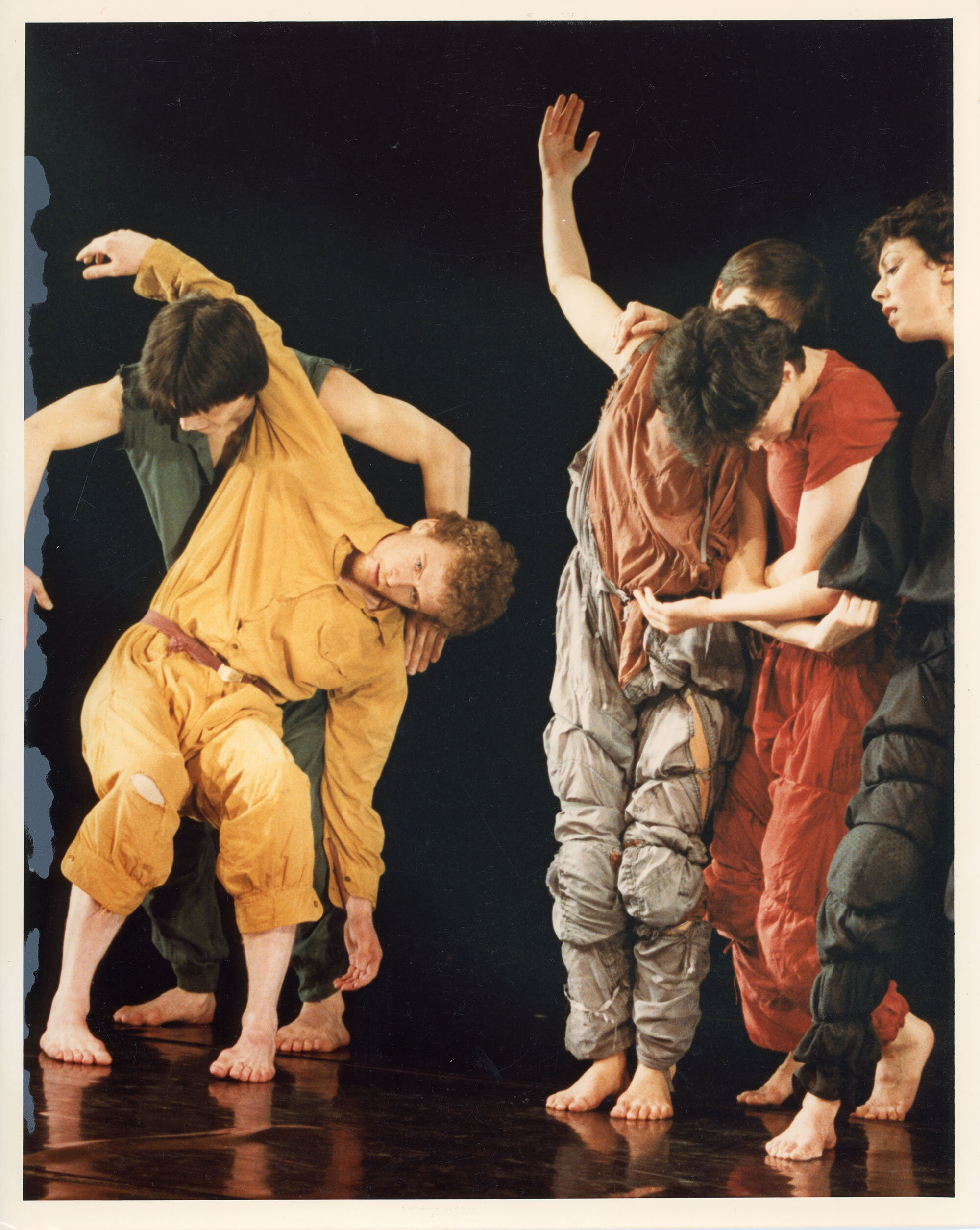

Lola Ryan: I looked at what they [the newspapers/critics] had said about how we got together. I don't recall. I think Karen [Jamieson] called me up and asked me if I'd like to be part of it so I must have worked with her prior to that, with her company I guess, so that she knew who I was. My first memories are of the studio, Terminal City Dance studio, working in that space together. That's what I really remember: the dimensions of the place, the Mahjong downstairs, wang-wang-wang, bang, and yelling, and things. The windows at one end, and how we worked in that small space. It was a kind of a very pleasurable pressure cooker, so to speak. And it was great because I came in, ready to work and do whatever was necessary. So again, it felt like a continuation. I think Coming Out of Chaos was the first formal dance work that I participated in as a dancer. Everything else had been self-directed and/or collective, but for Coming Out of Chaos, Karen [Jamieson] put us together. I wouldn't call us a company, but we were a cast with a purpose and a performance in mind; an end result that we were aiming for. So it was a compliment to be asked to be part of that. Though at the time, I just said: “Sure, I'll do that.”

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: You didn't know what you were getting into! [laughs]

Lola Ryan: Not really.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, yeah. And where was the Terminal City Dance studio located?

Lola Ryan: You know where the Sun Yat-Sen garden is? It was just a little bit to the West of that, I believe. That building’s probably gone. It was just off Pender St.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Oh okay.

Lola Ryan: As you come out of Chinatown and into the Downtown Eastside more.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Right. Okay. So, maybe on Carrall Street and Pender or something?

Lola Ryan: Yeah, Carrall Street. I think that would probably be the one.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Right, okay.

Lola Ryan: It was upstairs. It was a bit smelly, cockroaches, but that's where Savannah and Terry lived. I mean, they lived in the back of that place. That was their home.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Do you have any other memories or impressions about when you were approached by Karen [Jamieson] to participate?

Lola Ryan: This is why I wish there was more documentation because I'm trying to remember how we worked! And for the life of me, I can't remember except reading what was being said, it seemed like we were enfants terrible. We just wanted to do our own thing. I think Karen [Jamieson] saw us not as loose cannons, that we had our own way of doing things because we'd already had some success in doing what we did. So, for Karen [Jamieson], I guess it was probably like herding cats to keep us all together. At least with [Peter] Bingham and me, I would think. Lola [MacLaughlin] and Barbara [Bourget] when she was there, Jennifer [Mascall], they were more used to the dance environment, say, than Bingham and I were. And I'm putting words in [Peter] Bingham's mouth, maybe he won't see it that way, but we came out of the flow of contact work and things, more than we did the formality of choreography and specific steps and this-and-that. Things that constitute modern dance. Also, Karen [Jamieson] had something very specific in mind, because I don't recall us sitting around and talking about or articulating. I never quite knew what was in her mind, what her agenda was throughout the process, so I just went ahead and did what I could.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Well, you were familiar with what you could bring to the table too.

Lola Ryan: I wasn't a rebel, but I had to figure out what my path in it was. How do I do what's necessary here, that contributes to the piece, that pleases Karen [Jamieson], doesn't piss her off, and gives her what she needs to create the work? I think what we would do, would be things that she would see and say: "Oh, okay, so you do that, okay. Well, we can use that." It was a work in progress. And when you say a work in progress, and you're talking to two irreverent improvisers, well, that's an interesting challenge in and of itself, isn't it? The improviser doesn't really care about repeating. The choreographer cares intimately about repetition and precision. So, we did come over to her side–to the dark side, as it were, and formalized what we did.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: For a little bit. Yeah.

Lola Ryan: Enough to create the piece. And repeat it.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Do you remember any specific reasons why you chose to participate in Coming Out of Chaos at that time?

Lola Ryan: Well, with [Peter] Bingham–I wouldn't say we were inseparable at the time, because he'd done other things, as had I, but we supported each other. We came in as the two of us, and it felt like an evolution, you know? I was interested in finding out where the work that I did would fit into this other context. Into this other, more formal, more “modern dance” context, though I'm not sure that Karen [Jamieson] would have called it “modern dance” herself either. Karen [Jamieson] was always looking for something outside the framework of modern dance because of her interest in things that were more anthropological and more tribal than just typical modern dance concerns, which was fine with me.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Do you remember what was the most challenging part about developing this piece?

Lola Ryan: You know, to be honest, I don't. I mean, there were times when we had to make sure we were at the right place, at the right time, doing the right movements, but that was simply a question of learning. And there was nothing in the piece that was so far beyond my capabilities that I thought, “Oh, I don't know if I can do this.” That said, it may have been that Karen [Jamieson] worked with both our possibilities and our limitations within the piece, and that's a question that I couldn't answer because I'm not Karen [Jamieson]. Because as I said, herding cats meant she had to negotiate a whole bunch of interesting personalities in that piece. But, to answer your question, it never felt like something that was insurmountable, as something that I really had to go home and think about and study and work on and practice. We'd just come in, and work, and we built it.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, definitely. What was one of the most meaningful parts of developing this piece?

Lola Ryan: If I think about the piece, I don't remember what I did in detail, but I do remember that my connection was more with [Peter] Bingham and Ahmed [Hassan]. I remember them more than I remember Lola [MacLaughlin] or Jennifer [Mascall]. It was like we created a landscape, and Karen [Jamieson] went through it, she explored it. That's one read of it. She sat on her ladder, and then stood up, and watched this chaotic landscape, and then she went down, and she went through it, she explored it. So my experience felt like it was [Peter] Bingham and I working on things. There was a trio that Ahmed [Hassan], [Peter] Bingham, and I did which was very rhythmic. There was a hand-rhythm thing that Ahmed [Hassan] had taught us and then we did this back-and-forth. It was like a do-wop kind of thing, back-and-forth. Very interesting. And then that dissolved and it kind of exploded into something else. I'm sure the other dancers will have much more concrete memories of these events than I do. I do remember standing against the wall for some reason and punching the wall. It was a concrete wall with plaster over it, and by the time the rehearsals were over, I had punched a hole in the wall with my bare fist. Don't ask me why I was doing that, but it was something about the piece, it was pushing the edge. Coming Out of Chaos and doing chaotic things–irrational things in a sense. Looking at it rationally, it looked like it was chaos.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, yeah, definitely.

Lola Ryan: And quite often in the middle of it, you adapt, you adopt, you develop a chaotic frame of mind, you know? You're kind of in an asylum here. You're knocking against the walls, which I literally was doing. I don't know where that ended up in the piece but I remember making a hole in the wall. I think I ended up doing it on stage but just into open space.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Mm hmm. Barbara [Bourget]'s memory was of you and her sitting in the kitchen, and you telling her that she needed to eat for lunch. She was eating crackers. That was her memory.

Lola Ryan: [laughs] Really?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah.

Lola Ryan: There you go.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: She needed a better lunch! [laughs]

Lola Ryan: Yeah, yeah. Well, we were being more holistic at the time.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: [laughs] Yeah.

Lola Ryan: Though I shouldn't say that. Because years later at EDAM, I would eat nothing all day.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Oh, gosh. That’s not good.

Lola Ryan: And everybody else would be just chowing down to beat the band and I would eat nothing. Of course, I was a distance runner. I was like a wisp.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, yeah.

Lola Ryan: I ran to the studio. I ran there, I ran everywhere. To all the rehearsals and classes...

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: So much energy! I was wondering, what did you take away from working on Coming Out of Chaos that may have shaped or influenced your practice today?

Lola Ryan: Ah, well, I think indirectly–I mean, I really enjoyed creating something with a group of people. I'm a big fan of ensemble creation. And not that that was ensemble creation, but we were all together working on something to present, to perform together. So, I really liked the companionship of it, even though it wasn't really a cohesive group. To be honest, at the time, I don't know where Jennifer [Mascall] was. [Peter] Bingham and I were kind of a duality. Ahmed [Hassan] and Lola [MacLaughlin] were in a relationship. So, there were little affiliations within it. And Karen [Jamieson] was always thinking. She would stop and just look off into space and think, and think, and think, and then we'd go and do something. But what she was thinking, she wouldn't tell us. I wouldn't say there's anything directly that comes from that, of Chaos, so to speak, that shaped my practice today. I think if anything, it helped me understand the dynamics of creation on that scale. And I subsequently did do my own performances that were on that scale, with seven dancers and a longer piece that Jeff Corness was involved in too, so there’s that.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Would you say that it played an influence in starting EDAM?

Lola Ryan: That's a big question, isn't it? Well, let's put it this way, Coming Out of Chaos was the first time that we were all in the room together, the forming, with the exception of Jay [Hirabayashi] and Barbara [Bourget] who was there for some of that. But the rest of the time, that was EDAM working there. And of course, if you read what [Peter] Bingham says, and what Jennifer [Mascall] says, they both claim that they're the ones that had the idea to make EDAM. I don't know which one. I don't really care whose idea it was, all I know is that it came out of Coming Out of Chaos; became EDAM in its own way, without any sort of subjective thing. Just that that was the time when we got to know each other, and it was very mutually beneficial for us to band together and join forces, strengthen numbers–again, because EDAM presented such a wide range of material and approaches, from improvisation and contact, to Lola [MacLaughlin]'s work in sort of more German Expressionism, Jennifer [Mascall]'s improvisation and contact work and her technical work, Barbara [Bourget]'s ballet. So we were an interesting blend of people that Karen [Jamieson] put together. Again, I sometimes wonder what kind of image she had in mind, putting that kind of disparate group of people together to create something that was cohesive? Maybe she understood chaos right there [laughs].

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: It certainly was the formula for it! [laughs]

Lola Ryan: Yeah, yeah. But EDAM was seven artistic directors, so it was seven cooks trying to make one broth. There’s no question about it, it was a very exciting time, but frustrating as hell. Of course, for everyone, I think.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Mm hmm. And then when to know when your time was done there, when you need to branch out.

Lola Ryan: Afterwards, when EDAM toured, it was [Peter] Bingham and I who always got the great reviews, and the others were mentioned and described, but I think there was a degree of resentment, because they said, “Oh, well, you guys were just improvising.” So, we were discounted, it wasn't like actually choreographing and staging, and all that. Each year, we would give our piece a new title, and go out and perform it and we brought in Ahmed [Hassan] to one performance, put him onstage, blindfolded, with his berimbau, and [Peter] Bingham and I danced, and he couldn't see us. He could only hear us. And we worked together like that.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Neat!

Lola Ryan: We broke all the rules. Let's face it.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Yeah. That also brings me to my next question of any more memories that you have of working with Ahmed Hassan and Lola MacLaughlin.

Lola Ryan: Lola [MacLaughlin] was very precise. Again, quite private. Much more formal than I was. I don't recall within the piece whether she and I had any interactions. We must have had. This is why it's so confounding to me to think about Coming Out of Chaos because there's not a lot of concrete memories and images of it, in relationship to, say, Lola [MacLaughlin] or to Jennifer [Mascall]. So, Ahmed [Hassan] was there more as a musician, and he could move somewhat, but at the time, Ahmed was having problems with his legs, and they would give out on him, and we didn't know why, and he didn't know why. So, we kind of took care of him. He couldn't dance with us in the way that, let's say I could trust Peter [Bingham] to take my weight, or he could jump on me, or whatever. We couldn't do that with Ahmed [Hassan]. But we loved his spirit, and also Ahmed [Hassan] was a very political person. I mean, his background, his concerns were not just dance concerns, they were more social concerns as well, which I really respected. Anyway, I got along really well with Lola [MacLaughlin], I have to say, even though we were quite different. Lola [MacLaughlin] and I had a nice connection. The first time she saw me, I was doing a solo that Jennifer [Mascall] choreographed for me called 1947 Rambler Sedan Opaque. And I dressed as a businessman, with a suit and a briefcase. And that was the first time Lola [MacLaughlin] ever saw me. And she said, "Oh, that's cool. A businessman who dances."(3)

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: [laughs]

Lola Ryan: Yeah. But of course, that was just an act. Lola [MacLaughlin] and I had something in common in the sense that we were always thinking about things, and writing, reading. She was interested in German Abstract Expressionism. The whole DADA, Bauhaus context, which I knew all about as well. Though, just from studying, for my own interests, but she had really gone into it in depth, and that informed her work which was quite wonderful.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Do you think a work like Coming Out of Chaos would be made today? Why or why not?

Lola Ryan: Well, a work like that would require too much money. It would have to be produced and co-produced, and I just think there's too many impediments. Money is tight these days. You have to have all of your ducks lined up in terms of documentation. Everybody's resumes have to be up to snuff. You can't just bring somebody in off the street. Well, you can if they're a hip-hop dancer, a break dancer, because that's in. At the time, it was an easier thing than it ever would be today.

Paula Ross did a piece called Coming Together – I believe it was in the early ‘80s–and it was based on a piece of music by Frederic Rzewski about the Attica prison uprising in upstate New York in the ‘70s which ended up with the death of forty-three prisoners. But the piece was nineteen minutes of absolute, utter choreographed chaos. It was a prison riot for nineteen minutes. I wrote a profile of Paula Ross and I described that piece because it was really quite something that she did. She was a bit of a renegade too. And this piece was chaos, but it was very formal. She had a company. I've actually done the piece with my dancers, but just in rehearsal and improvised, and they're not trained dancers, so I don't know where it would go, but I'm interested in doing that kind of work. Whether I could do it to perform it on tour, that is another question, but I'm interested in that same kind of work. I'm interested in pushing the boundaries, the edge of things. And that's what Karen [Jamieson] was interested in doing too, like going to places, the less visible places of the West Coast, Indigenous art, which I think was part of it. But Karen [Jamieson]'s interests were nascent at the time, and looking at the body of work she's done since, I can see how Coming Out of Chaos was one of those pieces that was – it was actually the major piece after she left Terminal City Dance, I believe.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, I can verify that.

Lola Ryan: So, that was her finding her own ground and her own rhythm, and her own direction. So, hopefully we contributed to that for her because of course, she's gone on–she never stopped. None of us did. We kept going.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: I know. It's amazing. Just to jump back and follow up to that last question there–and maybe you'll have an interesting point of view on this given your writing background as well, but how do you think a piece like this would be received by audiences and dance critics or other dancers and choreographers today?

Lola Ryan: To be honest, sometimes I don't think dancers are the best people to watch this type of stuff, and today, the demographic is so wide for who comes to dance, or to theatre, or to poetry. You never know who's going to walk in the door. When [Steve] Paxton talked about the audiences for contact, he said the people who are drawn to it were more of the visual arts people because “they understood its inherent plasticity,” as opposed to dancers who are quite often looking for form and composition. Things like that. So today, the boundaries in the disciplines have basically blurred now–the Canada Council is trying to do that, you know, taking people out of their silos and going into interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary categories, so the audiences would be that. And I think today, because, of course, we're in the post-punk time, anything that sort of goes up against social norms or politically correct behavior, the sort of soft white underbelly of civilization, which I think Karen [Jamieson] was looking at in some way, there would be an audience for that. But again, it depends on who holds the purse strings to allow it.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, yeah. Very true! [laughs]

Lola Ryan: Yeah, sure we'd like to show you something radical, anarchist, feminist–would you fund us please?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. [laughs]

Lola Ryan: Yeah, to criticize everything that this culture is based upon.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Exactly. Yeah.

Lola Ryan: But I believe that any work like that always has value because it forces you to question the norms and the assumptions by which you live, or by which society operates. And, to be honest, when talking to you, I was thinking, how did that piece end? What was the final thing that happened? So, our memories are going to be highly selective in that respect.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Leading into my next question, what kind of questions do you think should be explored through this form of oral history when telling the Coming Out of Chaos story?

Lola Ryan: As I said, the piece was 40 years ago, so it will be kind of a time capsule: What was the environment? What was the context within which something like this piece arrived? And again, I would be interested in how Karen [Jamieson] came to this. I know it was a commission from SFU through Grant [Strate]. I don't know if she was given carte blanche to create something or whether they had something in mind. Simon Fraser being a bit of a hotbed of innovation–politically, as well as socially, but that was in the ‘70s, not so much at the time we're talking about. So, the piece, the oral history, would be interesting because if it's laid out clearly, people will understand the difference between then and now, and therefore, find out, how did that piece happen? And how did it affect what happened subsequently? Because I don't know myself what the repercussions, or the results of Coming Out of Chaos were, except to say that EDAM was born by-and-large out of our first associations together in the studio with Karen [Jamieson]. So, that's an interesting story in and of itself, the story of the dancers and why that piece was significant for getting us together, and what kept us together beyond Coming Out of Chaos.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah, definitely. And then following up on that, are there any particular kinds of stories that you would want to hear covered through an oral history, or in your opinion need to be told?

Lola Ryan: Are you talking generically, or about this piece?

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Maybe a little bit of both, even.

Lola Ryan: Well, I don't know if what I've said has provided the germ of a story via the details that I've mentioned, or the thoughts that I've mentioned. I think in terms of the Vancouver evolution of it, the story of dance in Vancouver, and how that worked; the disparate forces that Karen [Jamieson] brought together to create that piece, and then how we all dispersed into something else, into EDAM and elsewhere, because EDAM spawned 4 other companies. Let’s put it this way: Coming Out of Chaos could be seen in the light of subsequent events, as a bit of a crucible – a lot of energies, a lot of personalities put together into a room for the better part of a year. And we forged something that is obviously still worthy of conversation, as we're doing right now, and it spawned more than that. So, the story is about the evolution of identities of the people who were involved, the coming together, and then the dispersal into a new organization aka EDAM. Terminal City went its own way, Karen [Jamieson] went her own way, so a lot of things happened. I guess it's just the dynamics of the dance culture of Vancouver at that time, and where it went. So, I would say that Coming Out of Chaos was instrumental in the forging of that in some respects – not intentionally, but that was the result. So, that's a story in and of itself. Somebody mentioned that EDAM was the “super group of Vancouver”–I think it’s in Peter’s book [The Man Next Store Dances: The Art of Peter Bingham by Kaija Pepper] which is really interesting that Karen [Jamieson]'s work brought us together, and then we went and created something that was on the national stage. EDAM was known. If I tell somebody here in Ottawa that I was a founding member of EDAM, they go “Oh!” So, it still has its significance. And again, to be generous, but not forcibly so, that's to do with Karen [Jamieson]'s first work, bringing us together.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Yeah. Karen [Jamieson]’s orchestration.

Lola Ryan: I see it like a funnel: she funneled us together and we were in this one tube of creation for a year, and then at the other end, we were spit out into the new world of Vancouver in the ‘80s. And at the end of the decade, I was getting ready to leave, never to return. So, that's how I would put it.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: That’s great. So, quickly, just to wrap it up, I was wondering if you had any resources, including people, or texts, or books that come to mind, that you'd recommend to continue researching this project?

Lola Ryan: I think getting this book called Sharing the Dance would be good. On the back cover, Cynthia J. Novack, the author, says: "Growing out of the ‘60s avant-garde and counterculture, contact improvisation is an experimental movement in modern dance that captures powerful artistic and social forces in transition." Change that slightly, you could say that Coming Out of Chaos was sort of in that same street. So, that book would be interesting, because – let me just see how much Bingham is mentioned in this one. I'm mentioned quite a lot in this one. There’s also a performance of contact improvisation on YouTube: Contact at 10th & Second. It was about ten years since contact had started, five years since I'd started, but in the video you can see the way we started very loosely, and then we ended up in the corner in a line. Then things evolved from there: people coming up and taking turns, joining the whole sort of organic flow of the performance that we created, without knowing what we were going to create. Those people in that performance were: Kirstie Simpson from England, Alan Ptashek from San Francisco, I was from Vancouver. We were from all over the place as well, and again, we came together, and we put on this piece, which I think is still kind of referred to as a very interesting document of contact improvisation at that time. It's another way of saying, “Okay, here's what we do.” But of course, there was no title. There was no theme. There was simply what it was. Early on in California, [Steve] Paxton and [the contact improvisers] got together and titled their work: You Come, We'll Show You What We Do. That was what they put on the poster!

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: That's great.

Lola Ryan: Yeah. Very different than Coming Out of Chaos. I also wrote a history of contact.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: I was just going to ask you about this: the 10,000 Jams Later: Contact Improvisation in Canada, 1975 to 1995 piece that you wrote.

Lola Ryan: That was published in Contact Quarterly. It was done for – what's the name of that...it was a dance magazine coming out of Alberta titled Dance Connection…

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: Is it Dance Connection? Does that sound familiar at all? That's the citation that I have here.

Lola Ryan: That’ll give you the context for contact for Canada and therefore how we fit into the history.

Emma Metcalfe Hurst: That's amazing that you wrote that. Thank you so much for sharing everything, Lola. I really appreciate it.