Chapter 1

Before Chaos

Before Chaos is the first chapter of Coming Out of Chaos: A Vancouver Dance Story and it begins before the beginning. More specifically, it begins with notable people, companies, places, programming, and workshops inextricably tied to Coming Out of Chaos and its members which helped shape the emergence of contemporary dance in Vancouver during the 1960s and 1970s, leading up to the creation of Coming Out of Chaos in 1982. In particular, this chapter looks at the legacies of Paula Ross, Anna Wyman and Max Wyman, The Centre at Simon Fraser University, Terminal City Dance Research, Norbert Vesak’s Western Dance Theatre, Linda Rubin’s Synergy Movement Workshops, Contact Improvisation, Fulcrum, Peter Bingham and Lola Ryan at the Western Front, amongst others.

Paula Ross & The Paula Ross Dance Company

Paula Ross (née Pauline C. Campbell), a choreographer and dancer of mixed-Indigenous and Scottish ancestry who originally trained in ballet and chorus performance, opened the Paula Ross Dance Company in 1965.(1) Today, the Paula Ross Dance Company is considered to be one of Vancouver’s original contemporary dance companies.

Dance historian Kaija Pepper describes the Paula Ross Dance Company as “a company of individuals,” and how Paula Ross was known as the “Poet of Dance.” Pepper also shares that while the company was “highly respected,” it was not as “high profile... with all the razzle dazzle” as other contemporary dance companies, such as The Anna Wyman School of Dance Arts (1970) and The Anna Wyman Dance Theatre (1973), which would emerge soon after Paula Ross started out. Instead, Kaija Pepper characterizes the Paula Ross Dance Company as “a smaller, quieter presence,” which wasn’t so much a stylistic choice as the result of funding disparities in the arts during this period. Even though it had a subtler presence, the lineages of the Paula Ross Dance Company are a tangible testament to her impactful contributions and legacy as a dancer, choreographer, and teacher in the history of contemporary dance in Vancouver.

Coming Out of Chaos members Jennifer Mascall and Barbara Bourget were early students of Paula Ross. Savannah Walling also recalls taking courses with her. Jennifer Mascall remembers first becoming aware of Paula Ross’ work through her piece, Coming Together (1975), and speaks of their first encounter in Vancouver, shortly after Mascall arrived on the West Coast from Toronto:

Barbara Bourget also danced for Paula Ross – little did she know how impactful that experience would become:

“I got a job with Paula Ross, because one of her dancers was pregnant. That's where I met Jay [Hirabayashi], and that turned my life completely around.”

Barbara Bourget and Jay Hirabayashi would go on to have a lifelong collaborative relationship and partnership as a couple and as co-founding members of EDAM and Kokoro Dance, amongst other performance initiatives in Vancouver.

As Barbara Bourget mentioned, Jay Hirabayashi was also an early student of Paula Ross. He began taking dance classes with her in the early 1970s:

Jay Hirbayashi credits Paula Ross and the teachers at the Paula Ross Dance Company as being the first ones to introduce him to dance, and recollects Ross’ rigorous training:

Tensions emerged in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s between the Paula Ross Dance Company and Anna Wyman’s School of Dance Arts and Dance Theatre, as the two companies found themselves competing for the same Canada Council funding. Jay Hirabayashi even recalls feeling this tension while he was dancing professionally for Paula Ross’s company and taking courses at Anna Wyman’s studio on the side:

Kaija Pepper attributes the tensions between Paula Ross and Anna Wyman to inequitable and unsustainable grant funding practices in the arts. This would eventually lead to the demise of both the Paula Ross Dance Company and The Anna Wyman Dance Theatre and thus, the unfortunate loss of two esteemed contemporary dance companies in Vancouver:

The Paula Ross Dance Company helped pave the way for the emergence of contemporary dance in Vancouver throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s in Vancouver and, in many ways, the contributions of Paula Ross go under-acknowledged, as noted by Jay Hirabayashi:

I have to say I do believe [Paula Ross] is one of the best choreographers that ever came out of Vancouver. People don't understand. She's another unsung heroine in terms of her work – it was extremely well-constructed and moving.”

Barbara Bourget recognizes not only the influence of Paula Ross and Anna Wyman throughout the 1970s and ‘80s but also the vitality of the era as contemporary dance began settling into itself locally, drawing from particular influences and producing distinct forms:

“It was a great time for the explosion of contemporary dance in the city. It really was. It wasn't just Karen Jamieson Dance Company, there was Paula Ross still, and Anna Wyman way over there in West Van, and then Prism Dance Theatre, there were so many. Ballet BC was not far off the horizon. There had always been Pacific Ballet, but Ballet BC came out of Pacific Ballet and that was coming on the horizon too. It was becoming much more of a cosmopolitan city, I think. And then the influences of the East and the South.”

Anna & Max Wyman Arrive in Vancouver

In April 1967, Anna (née Schalk) Wyman and Max Wyman immigrated to Vancouver with their two children, Trevor and Gabby, from London, UK. In retrospect, Anna Wyman and Max Wyman’s arrival would become a pivotal turning point for the nascent contemporary dance scene in Vancouver and across Canada at large.

Anna Wyman, a dancer, choreographer, and teacher who had trained in Austria and England, went on to develop a unique style of contemporary dance that privileged improvisation, but also integrated her rigorous ballet and modern-dance training with theatrical elements, such as costumes, lighting, film, and lasers.(2) Her choreographic repertoire showed an interest in using dance as a form of social and political commentary that also drew in spiritual elements and featured impressive displays of athletic ability.(3)

In 1970, Anna Wyman opened the Anna Wyman School of Dance Arts in West Vancouver. She established The Anna Wyman Dance Theatre as a professional company in 1973, shortly after the troupe presented a series of performances under the name Anna Wyman Dancers at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1971.(4) As an established company, The Anna Wyman Dance Theatre went on to receive operational funding from the Canada Council for the Arts. In 1975, the company became the first professional contemporary dance company to tour across Canada and they also toured internationally to Europe, India, China, Europe, and Mexico.(5)

Kaija Pepper recalls a strong sense of local pride for Anna Wyman’s success as a trailblazer of many “firsts” in contemporary dance in Vancouver and across Canada:

Shortly after arriving in Vancouver with Anna Wyman, Max Wyman got a job as a reporter for The Vancouver Sun and eventually took the position of Music and Dance Critic in 1968. Wyman would go on to become an exceptional force for the arts in Vancouver and across Canada as a critic, historian, cultural advocate, and briefly, a local politician. Here, Wyman discusses his arrival to Vancouver, as well as his introduction to journalism and dance:

When The Anna Wyman Theatre Company went on tour, Max Wyman was hired on as the company’s stage manager. Wyman describes his time on tour as an invaluable and inspiring experience, both professionally and personally, as it deepened his appreciation for dance and writing as expressive and vital art forms:

Recalling the dance scene in Vancouver during the ‘60s and ‘70s, Max Wyman describes this era as “a time of tremendous ferment.” In particular, Wyman fondly remembers the plethora of creative events occurring up on the hill at Simon Fraser University, which were free to attend and served as rich material to absorb and review as a young reporter working for the newspaper. Wyman also recalls the emergence of the dance department as a part of The Centre for Communications of the Arts at Simon Fraser University:

Simon Fraser University would become one of the original creative hubs in the city, not only for contemporary dance, but also for interdisciplinary artistic experimentation throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. It also served as a meeting point for Coming Out of Chaos members, amongst many others, a site for dance training, teaching, and of course, formative introductions.

Simon Fraser University

Soon after it opened in 1965, Simon Fraser University became well known for the eclectic and radical activities regularly occurring on top of the mountain throughout the 1970s. It was a frenetic time of experimentation and exploration, and that vitality spanned across disciplines and departments to create a unique “scene” that had “a lively art vision,” in the words of Jennifer Mascall. Practitioners of music, theatre, film, visual arts, writing, and dance sought out opportunities to blend art forms together, and this creative energy drew people in as active participants and audiences for events, classes, and workshops which pushed against the boundaries of academic departments and the institution itself.

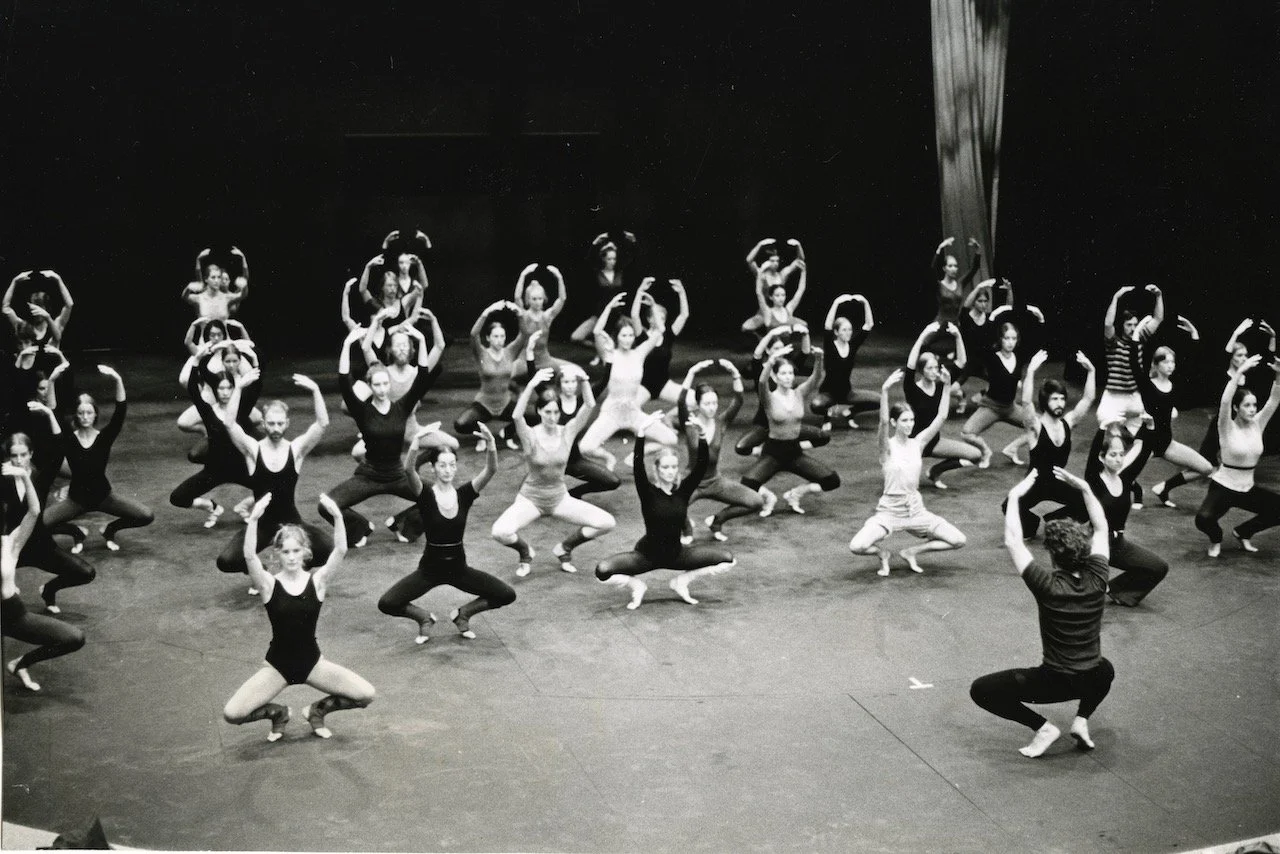

The dance program, initially an uncredited program that began in 1965, consisted of a dance club and a series of non-credit workshops run by Iris Garland that welcomed registered students and the general community.(6) Classes were held in the basement studio of Simon Fraser University theatre on the mountain. Iris Garland was a faculty member in the Physical Department Centre at Simon Fraser and she pushed hard to develop a dance department, which eventually established under the for-credit program and came to fruition in 1975 under the Centre for Communication and the Arts, known simply as “The Centre.”(7)

The Dance Department (via Iris Garland and administrator Nini Baird) invited many artists and dancers to do semester-long workshops and to do performances for the non-credit program. Garland, herself an American hailing from Chicago, regularly brought in international and American guests who went on to inspire and influence the emerging generation of dance students:

Savannah Walling also highlights key facilities for emerging practitioners at the university, specifically the Mainstage Theatre:

“Simon Fraser University’s theatre stage was an ideal venue for dance and it was accessible for emerging choreographers. You didn’t have to pay for the cost of the lighting equipment, technicians, and the venue. There was a willingness to try anything, and a formidable rigour brought in by dance artists like Phyllis Lamhut, exciting and very challenging.”

The Political Environment & the American Influence at SFU

The social and political ideologies of the ‘60s and ‘70s had a profound impact on the intellectual and creative activities that were occurring at Simon Fraser during this time, especially due to the strong presence of American students and teachers (many of whom were Draft Dodgers) that were present on campus.

“At that time, the Dance Department at SFU [Simon Fraser University] was starting as well and that was important. There were people working in the community that did come out of the SFU Dance Department. Certainly through SFU, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, a lot of the professors were American, so they brought that American story to Vancouver. I don't think there was too much sustained support for the Vancouver history of dance coming from SFU back then. Peter Dickinson might be changing that now, through his writing and interests, but in the past, historically, there hasn't been because I guess the early professors were from America, they knew American history, they didn't know Canadian history. They didn't know Vancouver history, so that's too bad. I can tell you even in the ‘60s and ‘70s that our artists were worthy of being talked about. Vancouver has always been known as a hotbed of dancers.” - Kaija Pepper

As a student himself during this era, Terry Hunter recognized the power of choreography and the body as a charged and symbolic site to make political and social statements:

People & Companies

Many other notable individuals were contributing to the dynamic environment at Simon Fraser during this period and many went on to establish acclaimed careers, collectives, and companies across the city and beyond:

Jennifer Mascall: “SFU was up on the hill in Burnaby at that time [1979], and Murray Farr had developed an international performance series that had no competition so everybody went there to see new work.”

Max Wyman: “There were certainly the theatre groups at Simon Fraser doing their own thing. John Juliani was the head of Theatre there and he was trying to develop a kind of elemental style of form, of movement – sort of [Jerzy] Grotowski crossed with Peter Brook. People lived their art. John [Juliani] lived his art. He and Donna, his wife, got married at the end of a performance at one of their shows.”

Savannah Walling: “The marriage of theatre director John Juliani and Donna Wong in January 1970 was both theatre and living ceremony: the story of their lives from conception to wedding day.”

Barbara Bourget: “Well, Iris Garland was involved in the actual Burnaby Mountain Dance Theater, but when it became Mountain Dance Theater, it was Freddie Long and Mauryne Allan. Mauryne Allan came out of Simon Fraser, she had trained there. Simon Fraser had [a dance program there], I think it started in 1975? So that opened up possibilities for people in this area of the world.”

Kaija Pepper: “Mountain Dance Theater came out of SFU, and they were very important at the time too. They didn't last long. There’s also Mauryne Allan, who was one of the founders, and won the first Clifford E. Lee choreographic award. That company [Mountain Dance Theatre] is under the radar now. Again, why? Because probably no one's written about them recently. One of the people involved in it [Mountain Dance Theatre] returned to the States. I think she was an American.”

In 1980, Grant Strate, who had developed Canada’s first dance program at York University in 1970, took over as the Director of the Centre for the Arts (now known as The School for Contemporary Arts, or SCA) at Simon Fraser. In the words of Jennifer Mascall, a graduate of the first program year at York University: “What an amazing impresario Grant has been for forming the choreographic life in Toronto and in Vancouver and in Canada.”

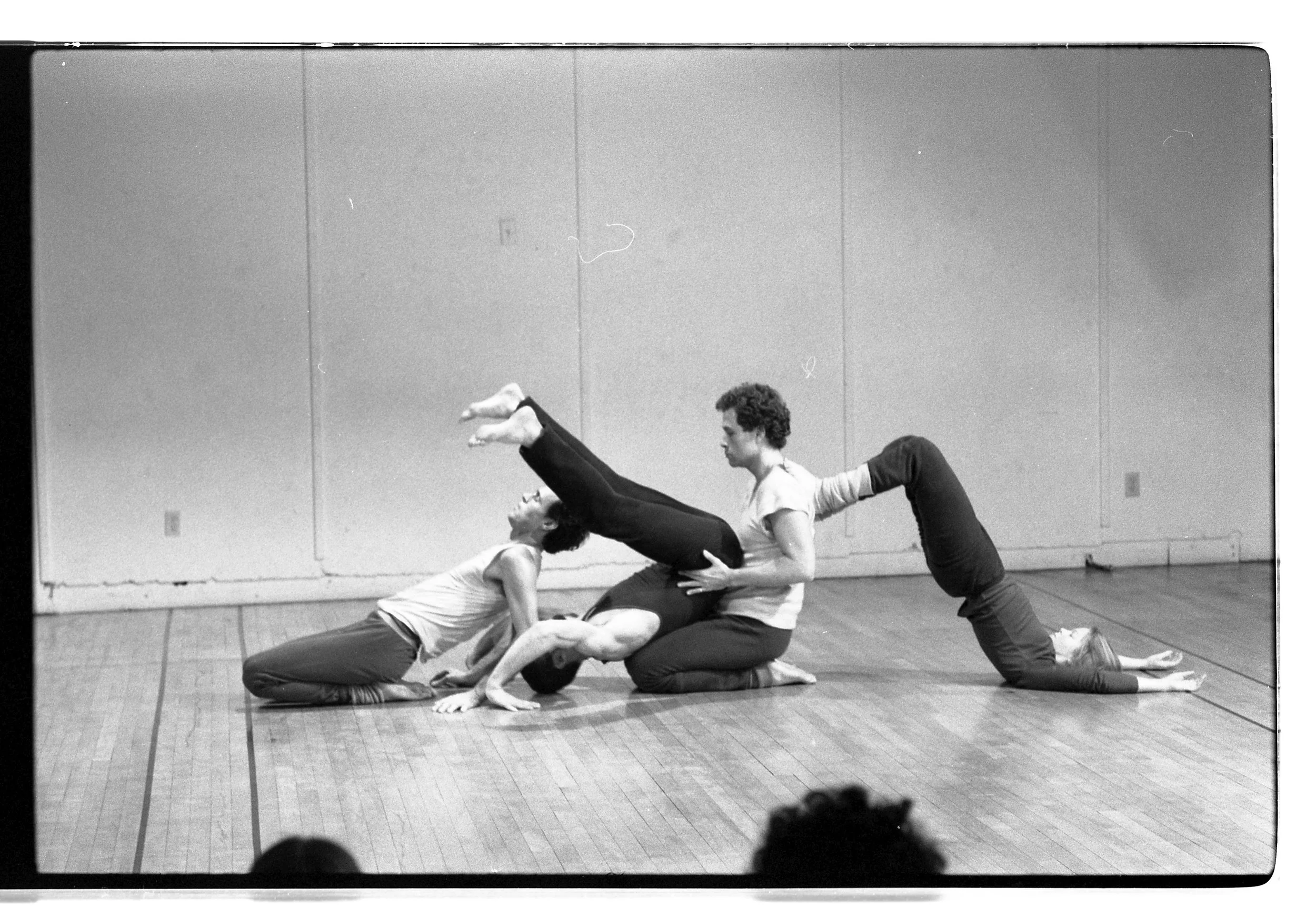

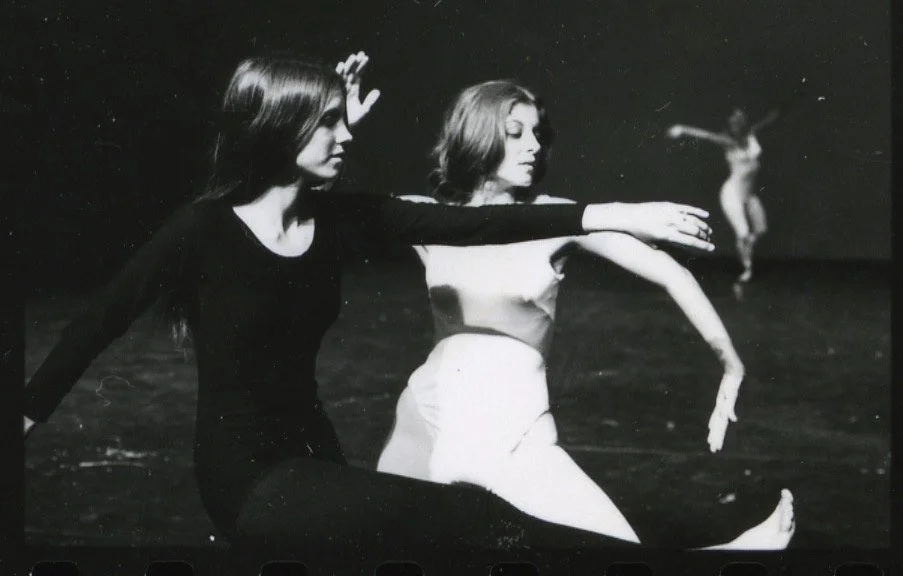

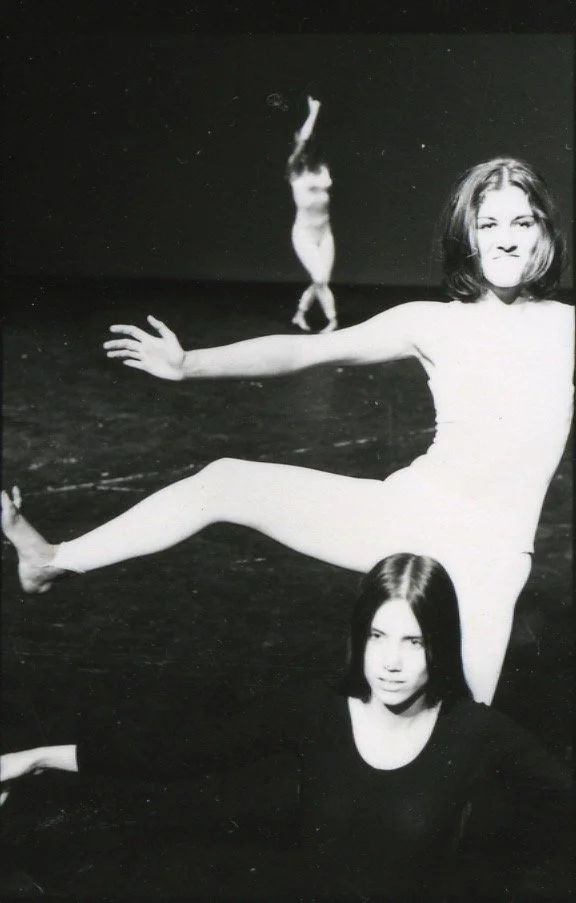

All images courtesy of Simon Fraser University Archives. Item reference number: F-197-4-0-0-9_052. Photographer unknown.

Summer Intensives with Phyllis Lamhut & Gladys Bailin

Karen Jamieson and Savannah Walling had started dancing together in 1969. However, it was in Phyllis Lamhut and Galdys Bailin’s Summer Intensives where Terry Hunter, Savannah Walling, and Karen Jamieson would eventually all end up and develop their deep appreciation for dance. This proved to be a fortuitous occasion for all, as it has since led to a lifetime of artistic collaborations and close friendships. Terry Hunter, Karen Jamieson, and Savannah Walling share their stories, noting the resounding impact of the Summer Intensives at Simon Fraser on their careers as professional dancers:

Savannah Walling: “...following a summer intensive workshop at SFU with New York dancer Phyllis Lamhutt, Karen Jamieson took off for New York City to study dance at the Louis-Nikolais Dance Theatre Lab in fall 1970. I followed her there after Christmas. The school was housed in a huge building called The Space, at 344 W. 36th Street, in midtown Manhattan’s garment district. The building also housed the Alwin Nikolais Dance Company, the Murray Lewis Dance Company and Joseph Chaikin’s experimental Open Theatre. Our teachers at the Louis-Nikolais Dance Theatre Lab included dancers Murray Louis, Alwin Nikolais, Phyllis Lamhut, Gladys Bailin, and the legendary Hanya Holm from Germany. The training went on all day long: technique, improv, and composition. Large classes – forty to fifty or more dancers. I used to go upstairs to see the open rehearsals put on by the Open Theatre of The Serpent and The Mutation Show. Life-changing to witness this physical theatre.”

Savannah Walling: “Although I was never a registered student at Simon Fraser University, my life has been interwoven with it. I started studying dance in 1969, at the non-credit dance program offered by the Centre for Communication and the Arts. I danced and participated in concerts as an emerging and faculty choreographer. I also dropped into workshops taught by theatre resident John Juliani, attended music and mime workshops. And I took the dance intensives taught by Danny Grossman, Judy Jarvis, Gladys Bailin, and Phyllis Lamhut. Karen and I presented a concert of our choreography at the SFU Theatre in 1974. As a sessional lecturer in dance from 1975-1979, I taught dance technique, improv and choreography – both credit and non-credit courses.”

Teaching at Simon Fraser University

Local dancers and choreographers - many of whom came out of The Centre - were able to generate an income by teaching workshops and doing sessional work at in the Dance Department at Simon Fraser. Dancers also took odd jobs around campus to support their practice, as was the case for Savannah Walling, who worked as a library clerk at the SFU Library, and Terry Hunter who worked as a dishwasher, theatre technician, and musical accompanist.

Savannah Walling: “After I got a job as a library clerk at Simon Fraser University [SFU] on Burnaby Mountain, I enrolled in the non-credit dance workshop that I discovered. My first teacher was Anna Wyman, who replaced Iris Garland who was on sabbatical, and I continued with Iris Garland after she returned. The non-credit contemporary dance workshops were housed under SFU’s Centre for Communications and the Arts, along with music, theatre and film programs. These free workshops attracted dancers of all skill levels from across the city. Such an exciting opportunity and life-gift when I think back to those days. While I was working in the library and studying dance at SFU, I also dropped into theatre workshops taught by John Juliani, founder of the Savage God Theatre Company.”

Savannah Walling: “Karen [Jamieson] returned to Vancouver after performing with the Alwin Nikolais Dance Theatre, and began teaching dance at SFU. At some point, Karen [Jamieson] invited me to assume some of her dance classes, so I became a sessional lecturer in contemporary dance up on Burnaby mountain from 1975-1979. Memories tumble together… all the years Karen Jamieson and I were involved in dance together. We danced in each other’s choreographies at SFU’s concerts of student and faculty repertoire.”

Terry Hunter: “I actually got into the theatre at Simon Fraser because I was looking for a job one day and I walked by the theatre and there was a sign outside that said "Audition at Two O'Clock." And I thought, Hmm, I've always wanted to act and really admired people that had the courage to do that. So, I went to the SFU employment office, I applied for a job, I think I got a dishwashing job [laughs], working in the cafeteria as a dishwasher, and then I came back at two o'clock and I got an audition and I got a part in the play! My call was the following week, and I showed up at the first rehearsal, actually it might have been the second rehearsal, and I said to the actor beside me, "When do we get paid?" If he knew what I'm doing now, he'd just laugh. He said, "Man, you don't get paid for this, this is a workshop." "Oh really? I thought this was a paid job." So, welcome to the arts! [laughs] But I was having a great time, I actually remember saying, "Well, I'm having a great time and I'm staying." I really did think it was a paid job [laughs]. And from there, because I got to work in the theatre, in that show, I started working as a technician. I was available to actually get paid as a technician in the theatre. So, I started doing that, hanging around the theatre more, getting to see more and more of the people, getting to know people.”

Lola Ryan: “I applied to teach there... I taught a series of Contact classes. I wasn't involved in performances or any other aspect of the running of The Centre. I did interview Grant [Strate], but other than that it was just a place, another venue to teach… I went in and taught young dance students. Tom Stroud was there, Darcy Callison... a lot of people who went on and did other things, but basically I was there to teach them some contact improvisation because they realized it was a necessary part of dance training, as it is today. It's now taught at the National Ballet School too.”

Barbara Bourget: “[I] actually taught at Simon Fraser for about eighteen years on and off, so I built a relationship through that process, being a teacher. I did my MFA there, too. So, I've had a [long] relationship with [SFU ]– not so much now, but I did up until 2004, I think.”]

Jennifer Mascall: “I think in the ‘80s and ‘90s, I was occasionally a sessional at Simon Fraser [University]. I think there was a year that Barbara [Bourget] taught one course and I taught another course during the ‘80s, but no, I wasn't really connected with Simon Fraser [University]. Grant [Strate] brought in the choreographic seminar there one year. I went and taught a workshop to the people there, but no, it wasn't wasn't part of my life.”]

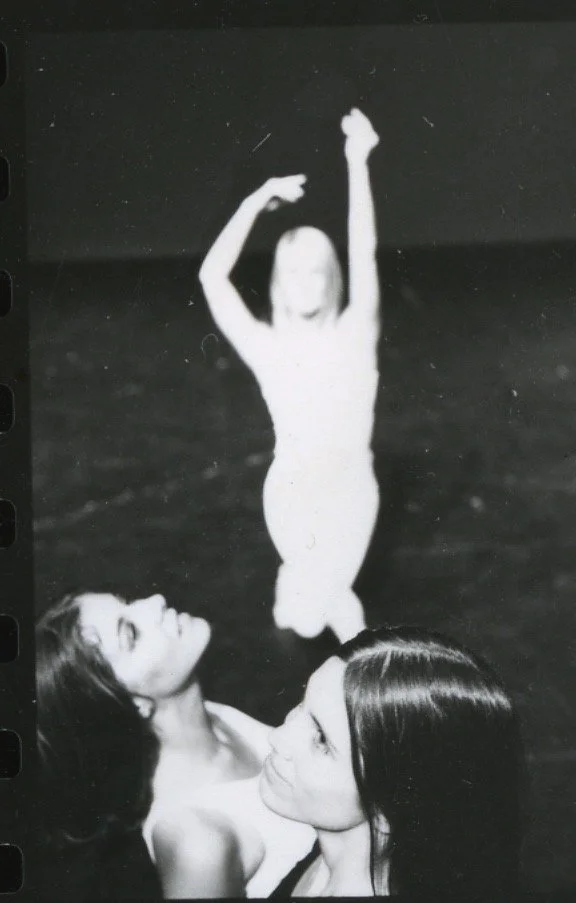

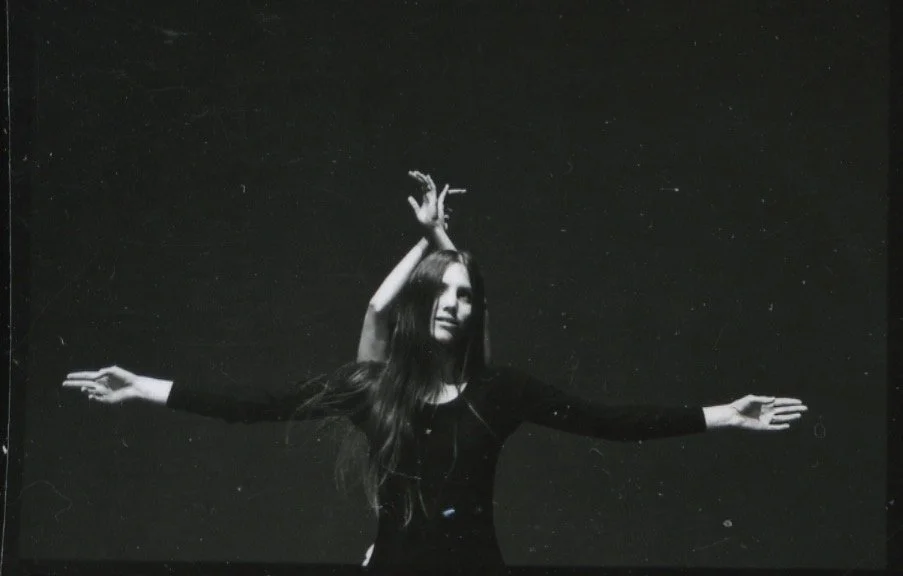

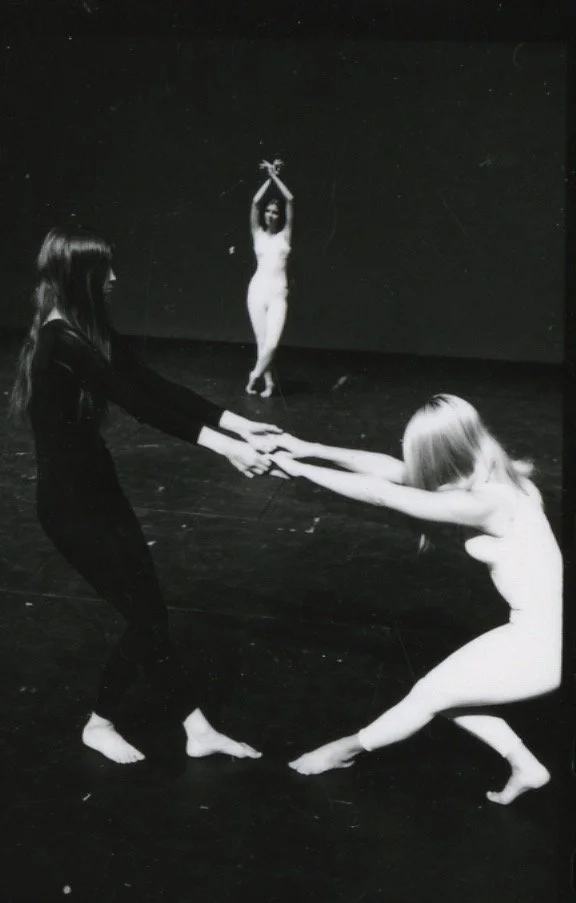

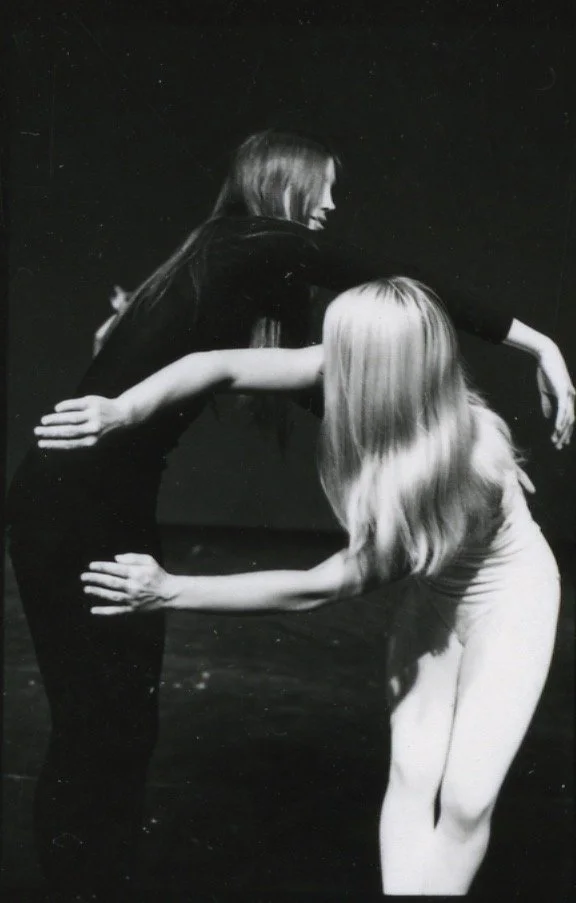

All images courtesy of Simon Fraser University Archives. Item reference code: F-197-4-0-0-9_049. Photographer unknown.

Terminal City Dance

It was out of this charged environment at Simon Fraser University, specifically the Dance Department and the Simon Fraser Mime Troupe, where Karen Jamieson, Terry Hunter, and Savannah Walling first came together. Terry Hunter describes meeting Savannah Walling and then Karen Jamieson:

“…the Simon Fraser Mime Troupe, at that time, they had an OFY grant, Opportunities For Youth grant. And this was money that the federal government under the Trudeau government, at that time, was giving to young people to do all kinds of things in the community. It was amazing funding. As a young person, you could apply for a project, or a program, and so Simon Fraser University Mime Troupe got some funding to do theatre mime shows in the park in Burnaby. I got a part in the show, and Wendy Gorling was a member of the troupe. She had a falling out with the other leaders in the group and she left the company and that's when Savannah [Walling] came in, so Savannah [Walling] replaced Wendy. I had known Savannah from a distance because I'd seen her performing on the stage and was quite – I have to say infatuated by her [laughs], from a distance, so I was pretty thrilled when I found out that she was joining the company. So, that's where I met Savannah Walling, and then it was there that Savannah Walling was in the dance program at Simon Fraser University along with Karen Jamieson, and others, and she was choreographing and she asked me to be in one of her pieces, and I said yes!”

From there, Savannah Walling, Karen Jamieson, and Terry Hunter went on to found Terminal City Dance (later Terminal City Dance Research) with a group of peers, including Karen's sister, Marion-Lea Dahl, as well as Hugh McPherson, Peggy Florin, Menlo MacFarlane, and Michael Sawyer. Terry Hunter recalls performing shows once a year for two years with this group at the Vancouver East Cultural Centre, before realizing in the second year (1976-77) that things were “…going really well and we liked what we were doing,” which led to the decision to officially form a company. At that time, the group didn’t have a name and billed themselves by the title of their shows, Dance Is… (1976) and Terminal City Dance in Performance (1977).

Hunter recounts the story behind the name, Terminal City Dance:

Terminal City Dance Rehearsal Spaces & Studios

In its early years, Terminal City Dance members struggled to find space to rehearse and perform. Karen Jamieson and Savannah Walling recount their resourcefulness as a troupe, and eventually, their success finding studio space in Vancouver to operate out of.

Karen Jamieson: “Well, let's put it this way, at the beginning of Terminal City, when we first began, we didn't even have a studio. We would run around and look for an empty room somewhere in the city, or a field, or anything, and rehearse, and practice there, and explore, experiment there. So we had no money. Nothing, nothing, absolutely nothing. Then we did find a little space and we all kicked in. So there was no salary. And so that influenced things, and [I] kept on teaching at Simon Fraser [University] to support my dance habit.”

Savannah Walling: “We began our rehearsals and training on the UBC Endowment [Land] grounds, in a grassy clearing encircled by forest, with space to move safely. Beautiful fall days. When the weather was turning cold, we snuck into UBC’s Old Auditorium at 6244 Memorial Road. When this turned problematic, we rehearsed for the rest of the year in Karen [Jamieson]'s living room in Kitsilano. I remember that before the Terminal City Dance ensemble formed, Karen [Jamieson] had a Gastown studio where we sanded the floors. Terminal City Dance also rehearsed briefly at the Mathers heritage house and grounds at 6490 Deer Lake Ave, Burnaby Arts Centre. After we left Karen’s living room, Terminal City Dance secured a rehearsal studio – a live-work space – in a warehouse at 260 Raymur Avenue, across from the BC Sugar Refinery. Terry [Hunter] and I took over the studio lease from musician Randy Raine-Reusch. The composer Elyra Campbell was our flat-mate.”

Savannah Walling: “I remember the floors we danced on in studios. We spent so much time rolling and going up and down from the floor, pressing our feet and softening our backs into the floor – I’ve always loved working on wood floors. The openness of the UBC Old Auditorium’s second floor, the openness of Karen [Jamieson]'s Gastown studio, brick surrounding, and big windows open to the port and the sea. Karen [Jameison]'s living room was such a small confined space, we had to shrink and condense choreography to fit into the room. Karen had a baby too. The Raymur studio was larger than her living room. It had a linoleum floor, bare walls with high windows – too high to see out of – and a raised area at one end where we stored musical instruments and tumbling mats. Across the street was the railroad track; sometimes the railroad bell got stuck and drove us crazy, ringing loud and long. We had a lot of privacy, and could be as loud as we wanted in our vocalizing, drumming, and improvisations, but we needed more space to move. A larger studio.”

Terminal City Dance eventually moved to the Lim Sai Hor Kow Mock Association building at 531 Carrall Street in Vancouver’s Chinatown in the Downtown Eastside. Having a studio space was a transformative for Terminal City Dance, as it allowed members to rehearse regularly and even served as a home for Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling to live in. The Terminal City Dance studio also became a community hub for new and experimental work in the forms of interdisciplinary activities and creative collaborations, emulating the early interdisciplinary ethos at Simon Fraser University. Terry Hunter highlights these similarities and the role of the Terminal City Dance studio as a community facility:

Similarly, Karen Jamieson acknowledges two other influences on Terminal City Dance: the local performance activities and media experiments happening at Intermedia and Jerzy Grotowski’s physical theatre in New York:

“Savannah [Walling] and I, with her partner Terry Hunter, started Terminal City Dance. And I think that may have come out of the interest of Terminal City in Intermedia. I mean, I started in this Intermedia milieu, and then in New York, we were quite blown away by the physical theatre going on. Kind of Grotowski-based – there's a guy named [Jerzy] Grotowski from Poland who did an extraordinary, fairly groundbreaking work in physical theatre that he brought to New York, and we were really taken with that.”

Terry Hunter describes the wide array of art forms being practiced within the studio walls, such as mime, mask, and clowning, as well as other cultural influences, but at the centre of it all was movement and dance. Music also had a strong presence in the Terminal City Dance studio, and musicians such as Ahmed Hassan, Sal Ferraras, Henry Kucharzyk, and Michael Smith were regularly brought in as collaborators.

Creature (1981) and Drum Mother (1982)

Terry Hunter as Creature. Composed, choreographed, and performed by Terry Hunter. Costume by Evelyn Roth. 1981. Photograph by David Cooper.

[L-R] Richard Fowler as Ama, Savannah Walling as Chamelea, and Terry Hunter as Drum Mother at the Aarhus Festuge, Denmark. 1985. Photograph by Jan Rüsz. Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling’s Terminal City Dance Collection.

Terry Hunter as Drum Mother. 1983. Photograph by Chris Randle. Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling’s Terminal City Dance Collection.

Terry Hunter as Ireme prototype at a Chinese New Year Parade in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Chinatown), on Pender St. January 1982. Co-presentation between Evelyn Roth and Terminal City Dance Research. Photo by Roland Donisi. Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling’s Terminal City Dance Collection.

Ahmed Hassan as Drum Mother (prototype), accompanied by performers at a Chinese New Year parade in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Chinatown), on Pender St. and Carrall St. January 1982. Co-presented with Evelyn Roth and Terminal City Dance Research. Photo by Roland Donisi. Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling’s Terminal City Dance Collection.

Evelyn Roth in the Drum Mother costume and others at the Terminal City Dance studio, 531 Carrall Street preparing for the Chinese New Year Parade. 1982. Co-presentation between Evelyn Roth and Terminal City Dance Research. Photographer unknown. Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling’s Terminal City Dance Collection.

The musical presence at the Terminal City Dance studio was particularly influential for Terry Hunter who began exploring the combination of movement and percussion, which led to him developing “percussion-based characters,” such as Creature (1981), and later Drum Mother (1982). These pieces would eventually bring his work out beyond the walls of the studio into the streets below.

Hunter describes the development of Creature and Drum Mother in more detail:

“Drum Mother (1982) led me to going outdoors so I became very inspired – this is when we were in Terminal City Dance – by the cultural traditions that were happening outside our door in Chinatown, on Pender street, and in the neighborhood where the line dancers are coming out, and the dragons are coming out, and there was hundreds and hundreds of people out there, and there were these mythical characters that were hundreds and hundreds of years old. I became really fascinated by cultural traditions that were embedded in the community and had been there for a millennia… a long time. At that time, we were doing a lot of work within the studio [as Terminal City Dance] and a lot of the work that we were doing was performing for other dance artists. Our audiences were very insular and small – it was a hot house, and it was very creative, but we were essentially performing primarily for other artists. I became very interested in the idea of taking art out into the community, so Drum Mother (1982) became a vehicle to do that, and Drum Mother (1982) actually appeared for the first time in the Chinese New Year's parade in 1982. Ahmed Hassan played the character. It [Drum Mother] was an unmasked character, but with this skirt and the drums in it, and we realized from there that it didn't quite work. We needed to cover the face up [laughs], because it didn't look mythical enough. It just looked strange. So, that character was developed. Drum Mother (1982) which then led to the creation of other characters (1983), which then led to appearances at the Children's Festival, and traveling across Canada to other festivals, and going international, and really doing work outdoors. That whole explosion of all that work, within the container of Terminal City Dance, grew out of that hothouse, but the hothouse became too small to contain all the visions and all the directions that the creative personnel within the organization were coming up with, right?”

The Performance Exchange Series

Another notable program that came out of the Terminal City Dance studio was the Performance Exchange program which was originally initiated and curated by Savannah Walling in 1981, and was later taken over by Barbara Clausen. The Performance Exchange program brought together choreographers and artists from a variety of disciplines to meet and exchange ideas through informal studio-performances. Coming Out of Chaos was even previewed as an in-process work as a part of the Performance Exchange series, alongside Dave Rimmer’s film, Portrait of Al Neil.

“We premiered my choreography Banana Split at a Performance Exchange hosted in the TCD studio. The composer was Elyra Campbell and the performers were Ahmed [Hassan] and myself. That same event also featured, among other artists, Jennifer Mascall and Lola MacLaughlin in their choreography, Rosebleed.” - Savannah Walling

Administrators of Terminal City Dance

With what little money they had, Terminal City Dance decided to hire an administrator, Joyce Ozier, who was later replaced by Barbara Clausen. Clausen recalls how she first got started with Terminal City Dance:

“At a certain point, I was approached by Joyce Ozier who had a grant to get an assistant. She was the manager of what was then Terminal City Dance: Terry Hunter, Savannah Walling, and Karen Jamieson, and she said, “Come on down!” So, I did. I think it was a half-time job or something. I had never done any administration at all. We worked out of Terry and Savannah's studio in Chinatown [laughs]. It was a zoo, a beautiful studio in the front, but it was their living quarters as well. I remember coming to work – and of course, in those days we had typewriters, not computers, and I'm coming to work and seeing Terry's socks on the typewriter [laughs], and, you know, going into the bathroom, and having to move their toothbrushes. I learned Arts admin the hard way. I did books. Joyce [Ozier] taught me how to do bookkeeping, manually. I think I wrote a couple of grants. Towards the end of the first year, she said, “Oh, by the way, I'm going on sabbatical with my husband next year so tag, you're it!” [laughs] So I went, “Ah... sure...!” Those were the days where you could go and get training at Banff [Centre for the Arts], or go to workshops that were really well supported, and well-presented, so I did a couple of those, but it really was like reinventing the wheel.”

Barbara Clausen was a profoundly impactful administrator and programmer for dance in Vancouver and was also an SFU dance department alumni herself who had taken classes with Anna Wyman and Santa Aloi, the first hire of SFU’s Dance Department. Terry Hunter recalls first meeting Barbara Clausen on campus where she expressed, early on, her vision for a centralized dance organization in Vancouver – a vision that would become prophetic:

“I knew Barbara Clausen from Simon Fraser University, she was in the [SFU] dance program, and I remember we were sitting around talking about what we needed in the dance community, and Barbara Clausen said – and I remember very clearly: "We need a dance organization. We need a dance organization that supports the dance community in the city of Vancouver." I think that time period had a huge impact on Barbara Clausen, and obviously, what she did with The Dance Centre, but also what she did in terms of the types of programming that she then started to do within the dance community when she established Dance Allsorts.”

In February 1982, Terminal City Dance became Terminal City Dance Research which marked an organizational shift. Terminal City Dance Research became an umbrella organization with three main areas of dance: The Performance Exchanges series curated by Savannah Walling, a dance company directed by Karen Jamieson, and dance collaborations by Savannah Walling and Terry Hunter. Additionally, Karen Jamieson became Artistic Director and Savannah Walling and Terry Hunter became Associate Directors.

After a year of programming, a meeting was held on July 6, 1983 with Savannah Walling, Terry Hunter, Karen Jamieson, and Barbara Clausen regarding the future of Terminal City Dance Research where it was determined that the group would separate. Karen [Jamieson] would go on to develop her dance company with Terminal City Dance manager, Joyce Ozier, and find a new studio and office space. Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling maintained the Carrall St. studio, and formed a new society to create work under which became Special Delivery Dance Music and Theatre in the Downtown Eastside.

Terminal City Dance Research was eventually handed off to Barbara Clausen in September 1983 after Joyce Ozier resigned. Barbara Clausen was elected as the new Director of the Terminal City Dance Research Centre and continued to program workshops and performance exchanges under the name Terminal City Dance Research. Notable programs included: the Performance Exchange series and the Independent Dance program. In 1985, Terminal City Dance Research, co-produced the 2nd Annual Dance Week at the Firehall Theatre, which included a program of independent performers from Vancouver and across Canada. In May 1985, Clausen left Terminal City Dance Research to take up a position at Canada Council for two years.

Just up the hill from the Terminal City Dance studio in Chinatown, a flurry of artist-run activity was also taking place at Western Front, which was home to Linda Rubin’s Synergy Movement Workshops and later, EDAM. Contact Improvisation also made its way into the dance studio at Western Front all the way from New York City.

Linda Rubin

In-between her third and fourth year of studies, Linda Rubin attended the Martha Graham Summer School in New York City. Following this experience and entering into her final year at the Vancouver School of Art, Linda Rubin began experimenting with designing improvisational forms and becoming curious about the process of putting bodies in space to create forms, asking not only what forms happen, but how do forms happen?

Linda Rubin entered dance as a young teenager after moving from Saskatchewan to Vancouver at age eleven. She took ballet classes with Kay Armstrong at the B.C. School of Dance and studied and performed international folk dancing. Linda was exposed to contemporary dance early on in 1963-64 while she was studying in Israel, and at the Vancouver School of Art (now Emily Carr University of Art & Design) from 1964-68. During her time at the Vancouver School of Art, she majored in Design where she developed concepts, language, spatial forms for ensemble improvisational dancing, multimedia works, costumes, set design, and printmaking. In between her third and fourth year of school, Rubin attended the Martha Graham Summer School in New York City (1966-1967), and studied and performed at Jacob’s Pillow University of the Dance (summer 1967). In 1968, Linda moved to New York to study and perform in the contemporary dance companies of Norman Walker, Dan Wagoner, and Deborah Hay. Returning to Vancouver in 1971, Rubin established Synergy Movement Workshops.

Western Dance Theatre & Norbert Vesak

It was also during the late ‘60s that Linda Rubin met Norbert Vesak, resident choreographer of the Playhouse Theatre and co-founder of Pacific Dance Theatre, after attending one of his performances. Linda Rubin credits Norbert Vesak as one of the influential figures who introduced her to the world of contemporary dance. The two found common ground in their experiences abroad in New York City as Vesak had trained with Jacob's Pillow and Rubin had trained with Martha Graham. Rubin and Vesak developed a close creative relationship and friendship. Rubin even helped Vesak develop Western Dance Theatre in West Vancouver, where she danced and choreographed with Norbert Vesak and taught classes.

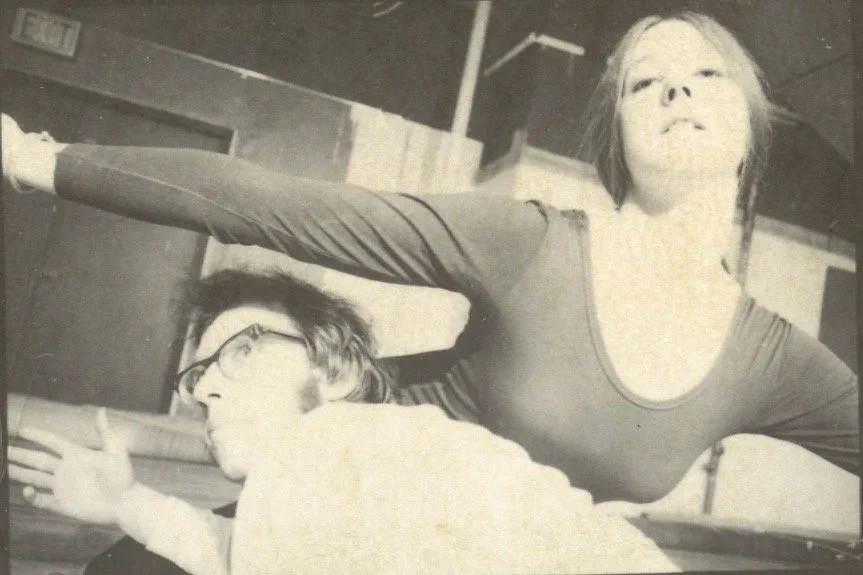

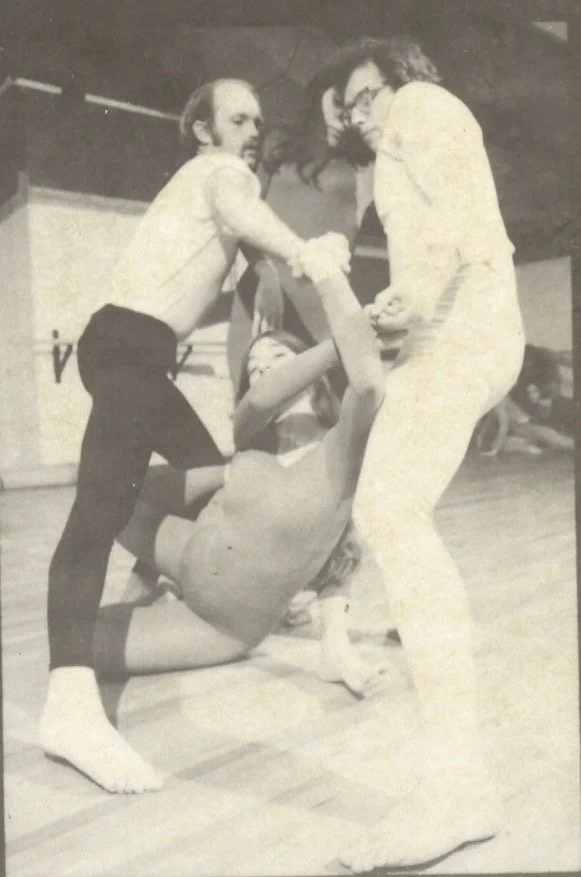

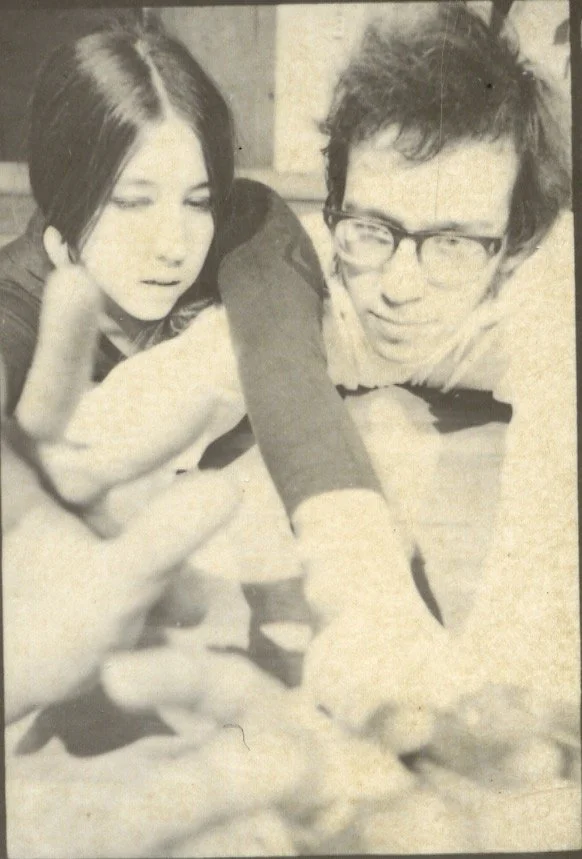

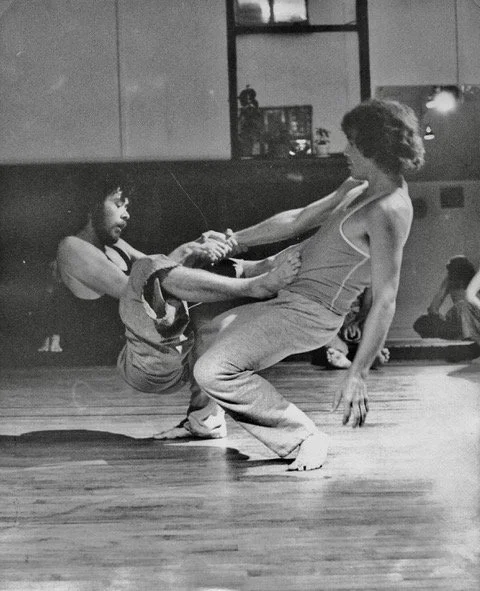

Improvisation Rehearsal. Seamus Linehan and Lola Ryan at Synergy Studio, Western Front. 1975. Photo by Carol Gordon. Linda Rubin, Synergy Movement Workshop Collection.

[L-R] Peter Bingham, Jane Ellison, Linda Rubin, and others at Synergy Studio, Western Front. 1976. Photo by Daniel Collins. Linda Rubin, Synergy Movement Workshop Collection.

Technique Workshop, Weekend Workshops. (L-R) Louis Gidzinski, Lola Ryan, and unknown at Synergy Studio, Western Front. 1975. Photo by Sara Wellington. Linda Rubin, Synergy Movement Workshop Collection.

Synergy Movement Workshops & Synergy Performing Association

After the dissolution of Norbert Vesak’s Western Dance Theatre, which was sold as a business to Anna Wyman in 1971, Linda Rubin went on to begin Synergy Movement Workshops in September of the same year with the intent to keep dancing, choreographing, and developing improvisational forms in dance. Linda Rubin describes her motivations to begin Synergy, as well as the inspiration behind the name and her objectives for the workshops:

Linda Rubin: “After Norbert Vesak sold his studio business to Anna Wyman, some of my colleagues who were also involved with Norbert were interested in continuing their teaching, and I was inspired to open a studio where we all could continue dancing. My objectives of creating and running a studio included the studying of improvisation as a dance form – which was very unique in 1971. Students could choose their own dance style for their class selection and if they were reluctant regarding improvisation and wanted to do just the technique classes, they could, or vice versa.

Linda Rubin: "As you may know, nowadays, the word Synergy is overused, especially as concepts for gas stations [laughs]. In 1970, I was doing some reading and I came across the word “synergy” and thought, “Well, that's exactly what happens in improvisation work!” I did further reading and discovered that the word is also a medical term. I adjusted the definition of Synergy to describe actions related to people. I describe Synergy as: "‘people come together to produce a combined effect greater than the sum of their separate actions.’”

Linda Rubin: “My basic objective was to create an adult-based studio environment that offered a variety of movement-based disciplines. People could study Ballet, Modern, Jazz, Improv, Tai Chi, or Yoga with professional teachers. The techniques classes had the normal objective of developing technical skills in the various dance styles. The improvisation classes had an objective of experimentation and developing ensemble work. Often, within the improv workshops, there were musicians and dancers collaborating and dancing together. There was certainly a clear objective of experimenting with the synergy between music and dance. Participants really loved to move freely, to share their experiences, and to discuss the process.”

Synergy members also occasionally performed under the name Synergy Performing Association, which was also the official name under which Linda Rubin received funding. Synergy Weekend Workshops was a name used to separate the performing group from the ongoing workshop classes. Linda Rubin recalls performances with Synergy Performing Association:

Linda Rubin: “We held performances “In Studio.” We had held performances in art galleries and public venues, but eventually I decided that offering intimate studio performances allowed us to experiment as freely as possible. Performing in the studio, or “underground,” gave me a freedom to experiment and to be unbound from the historic definitions of what dance is expected to be, and what, or who should be performing. Many others were in that frame of mind as well.”

Western Front

Synergy Movement Workshop classes were initially held at a studio space on Granville Street and Robson Street in Downtown Vancouver. Later on, Synergy relocated to Western Front, an artist-run centre that opened in 1973 in the former Knights of Pythias Hall, just off of Main Street on 8th. Western Front served (and continues to operate) as an active interdisciplinary live-work space for artists. It was home to a large dance studio on the main floor, as well as The Luxe, a historic 120‐seat concert hall upstairs that was often used by resident, local, and visiting artists for performances, workshops, productions, dinners, etc. Western Front was well-known for bringing in artists from abroad. Indeed, Linda Rubin recalls Western Front creating “a public program [that] centred on bringing in international artists, musicians, and dancers, like Deborah Hay, to Vancouver. During the days when Synergy was located in Western Front, Synergy dancers would participate in these events as much as possible.”

“The Western Front, to me, because that's where I went and where I did contact [improv], seemed to be the centre of the art world. The curators and programers there seemed to know artists from all over the world, they had a vision. It [was] like, they're really doing things!” - Jennifer Mascall

Lola Ryan and Peter Bingham

It was around this time, during the mid-1970s, that Lola Ryan and Peter Bingham, two future members of Coming Out of Chaos, got their start in dance by attending Synergy classes with Linda Rubin. Kaija Pepper and Savannah Walling also attended Rubin’s classes.

Linda Rubin recalls Lola Ryan and Peter Bingham in her classes:

Linda Rubin: “Lola Ryan joined Synergy before Peter Bingham. Lola was an athlete and she was deeply involved in running and competitive rowing before joining Synergy. She taught high school English and she would often adjust some of my language choices... a good thing. She was energetic, a leader, and highly analytical. In group discussions, and other conversations with me, she would instigate productive conversations surrounding the artistic and physical intricacies of the work. She worked diligently in the body work classes and became more physically released, flexible, and articulate. In the improvisation work, she was a positive contributor in advancing and evolving the main focus scenes. She had the patience to actively observe the work, as well as boldly make offers. Lola was fortunate to be a member of a group of dedicated dancers in Synergy at that time. In the late ‘70s, Lola began teaching contact workshops in the Synergy workshops schedule.”

Linda Rubin: “Peter Bingham joined Synergy during the Weekend Workshop Projects. He had an influential introduction to Synergy’s body work, improvisation, and philosophy via his participation in that weekend. I believe his exposure to the strong dancers in the project was deeply influential and there was no turning him off. Peter began his training with challenges to develop his physical flexibility and articulation. Peter would throw himself into the work without many intellectual or imagistic restraints. He had abundant desire. Peter possessed a natural movement-loving physicality, and he expanded his abilities quickly. He nurtured and evolved a resourceful circle of colleagues through the workshops. The work made total sense to him, he was excited, and I think he could sense his future directions. In the late ‘70s, Peter began leading contact improvisation, and children’s movement workshops in the Synergy workshop schedule.”

Linda Rubin: “I believe that both Lola and Peter were inspired, in large part, due to being able to dance with an adult group of generous people, with similar talents, and dedication to advancing the work. These people also wanted to be a part of new directions, and that created a sense of excitement, security, and comraderie. Similar to Peter and Lola, many other people had a deep level of commitment in advancing the work, translating Synergy concepts into their own voices, and creating their individual career paths.”

Similarly, Peter Bingham and Lola Ryan describe their entries into dance via Linda Rubin, Synergy, and improvisation:

Linda Rubin adopted values and formal elements from Contact Improvisation into Synergy workshops and classes. For example, Linda Rubin recalls prioritizing “free experimentation” and attracting untrained dancers of all genders and skill-levels to her classes. This approach was closely aligned with her desire “to develop a non-threatening, and caring style of teaching - non-competitive,” which was “quite the opposite” from her traditional training background.

Linda Rubin: “In the ‘70s – and I am not exaggerating – there were beginning level classes with thirty-five people registered, with approximately half women and half men participating. People were able to easily access, and find success in the work, and they really enjoyed dancing with each other. Many people formed enduring bonds.”

Linda Rubin: “The participants in the classes and many of the people who were performing “In Studio” were not traditional dancers. Some people created careers in dance, but generally most folks were living an active, healthy lifestyle, and wanted to engage in more artistic / expressive physical activities other than sports and fitness. Participants included professional people, students, performers, adults of all ages, and abilities. There was a time when Rajneesh devotees would participate in the classes, but most participants were from the general public.”

Linda Rubin: “I believe that because one could move freely and you could use your natural abilities – especially in the improv work, and you could advance your abilities with studying technical body work and dance training, the workshops inspired more men to become involved in this style of dancing. The workshops were filled with very, very interesting people….all keen on dancing together.”

Linda Rubin would later move Synergy Movement Workshops from Western Front to the Arcadian Hall (which would later become Main Dance Place in the ‘80s, operated by Gisa Cole), located close by at 2214 Main Street and 6th Avenue. Linda Rubin eventually relocated Synergy to Chalmers Church, near South Granville, before she left Vancouver to return back home to Saskatchewan in the Spring of 1982. In Saskatchewan, Linda Rubin continued to host workshops, choreograph, and teach students:

Linda Rubin: “After I moved to Saskatchewan I continued to run my own workshops and teach and choreograph for theatre and dance. A very special memory was when I was teaching workshops at 25th Street Theatre School, and one of the young actors was Shawn Hounsell. His talent was obvious and he was deeply interested in modern work. He was considering shifting career directions from theatre to dance. I encouraged him to study in my contemporary dance classes in the Department of Physical Education at the University of Saskatchewan. At that time he was also studying ballet and loving it. I gave him free classes in my privately run Synergy workshops as well. Soon, he was auditioning to attend the Royal Winnipeg Ballet summer school and then he moved to Winnipeg to study in the professional program at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet. Fast forward… Shawn is recognized as one of Canada’s internationally acclaimed choreographers.”

In 1993, Linda Rubin accepted a tenure-track position at University of Alberta teaching in the BFA Conservatory for Performing Actors program. She retired in 2009 and continues to work in professional theatre and dance in Edmonton, Alberta.

Contact Improvisation

In the mid-1970s, contact improvisation began making its way across the country and the American border from New York City over to Vancouver. Contact improvisation would go on to become a highly influential dance form and social and philosophical movement for the emerging generation of local dancers, such as Linda Rubin and Jennifer Mascall, but especially for Lola Ryan and Peter Bingham.

Steve Paxton, who was a dancer for Merce Cunningham with a background in martial arts and tumbling training, is cited as the original creator of Contact Improvisation.(4) In 1972, Paxton debuted a series of performances at the John Weber Gallery in New York City that included seventeen of Paxton’s students and colleagues, many of whom went on to practice and develop the new dance form. Nancy Stark Smith, who is also considered to be an early founder of Contact Improvisation, was part of Paxton’s original group.(5)

Lola Ryan remembers bringing Steve Paxton and Nancy Stark Smith to Vancouver, and hosting them at the Western Front for performances and workshops. Linda Rubin describes Steve Paxton and Nancy Stark Smith’s inaugural visit to Vancouver which was organized by the local visual arts community. Their performance introduced the keen group of emerging dancers to Contact Improvisation for the first time which subsequently had a resounding influence thereafter:

“In the mid ‘70s, Steve Paxton and Nancy Stark Smith came to Vancouver, and held an exciting public Contact Improv demonstration and we all went. That’s how we were first exposed to Contact Improvisation, and we just loved it, everybody loved it right away! I amalgamated the basics of Contact work into my work, and it became an important extension of my improvisational dance vocabulary. Historically, I was always working on improvising with an awareness of creating a choreographic aesthetic, and aiming for a main focus in advanced work. Integrating the Contact Improv work into my existing improv vocabulary was so natural and harmonious. The exposure to Contact Improv immediately inspired people like Bingham and Ryan. I believe Contact Improv transformed their understanding of what dance could be. People deeply interested in Contact Improv traveled for more training, usually in the states. Synergy co-hosted several Contact Improv workshops with John Gamble, Nita Little and a RE:UNION workshop, organized by Seamus Linehan, with Steve Paxton, Nancy Stark Smith, Nitta Little, Kurt Siddel, and Danny Lepkoff. Ryan and Bingham became highly skilled and deeply involved in contact work. They taught Contact Improv workshops within the Synergy schedule.” - Linda Rubin

In simple terms, Contact Improvisation is “...most frequently performed as a duet, in silence with dancers supporting each others’ weight while in motion.”(1) What results is a physical dialogue from the exchange of touch, weight distribution, and support between bodies.

Traditional dance training is not considered a necessity for performing Contact Improvisation, nor is muscular strength. However, strength can enable certain movements to be carried out and technical expertise is also beneficial in Contact as Peter Bingham acknowledges:

Contact Improvisation sessions often took place in informal, open, social gatherings known as “jams,” which placed dancers and audience members on an equal stage. This setting collapsed spatial hierarchies between performers and viewers and subverted the idea of dance as a performed visual medium; allowing for a synergy to emerge between the two groups.

Contact Improvisation is also considered to be a “social dance,” in that anyone could partake and learn it. Peter Bingham even suggests Contact Improvisation can be considered a type of folk dance. Lola Ryan also makes this connection:

Further, Lola Ryan describes how Contact Improvisation, in many ways, embodied a set of social values that “rejected traditional gender roles and social hierarchies,”(3) as well as a lifestyle that both she and Peter Bingham were deeply embedded in:

In Vancouver, Lola Ryan and Peter Bingham began creating their own unique form of Contact Improvisation. In the book Sharing the Dance: Contact Improvisation and American Culture by Cynthia J. Novack, Lola Ryan describes working with actors and using Contact Improvisation “...as a catalyst for performing scenes from Shakespeare.”(2) Here, Lola Ryan expands on her experimentations blending theatre with Contact Improvisation:

In the same book, an excerpt from a letter written by Lola Ryan in 1988 shares recent developments and choreographic experiments in Contact Improvisation that both she and Peter Bingham were undertaking. She shares:

“Peter Bingham has actually spent part of this year in going back to the basic form of Contact, stripping it of the inevitable accretions that years of work can apply...One of his primary reasons for doing this was, he said, to rediscover the place, or state, where the dance itself would carry the dancers through, rather than the imposed notion of “performing” Contact.”

Lola Ryan’s letter goes on to explain that the group has “been presenting more theatrically-staged work that is still largely Contact-based,”(4) and that Peter Bingham has been experimenting with using Contact in choreographed work. Lola Ryan also shares that she has “....been working on ensemble improvisation with a group of three actors and three dancers, using Contact as a metaphor for community and the social fabric.”(5)

Fulcrum

In 1977, Western Front became the home base of Fulcrum; a Contact-based group consisting of Peter Bingham, Andrew Harwood, and Helen Clarke, who did performances and workshops both locally and nationally. Peter, Andrew, and Helen Clarke were familiar figures at the Western Front, as all three participated in Linda Rubin’s Synergy Movement Workshops.

Jennifer Mascall, another future member of Coming Out of Chaos, recalls attending a workshop hosted by Fulcrum at Western Front in 1978 after the Dance in Canada Conference where she met Peter Bingham for the first time:

Following this experience, Jennifer Mascall describes her new vision of “a dream dancer” at the time, highlighting the generative qualities of blending traditional dance forms with Contact Improvisation:

Little did Jennifer Mascall, Lola Ryan, and Peter Bingham know, they would soon become part of an experimental amalgamation of not only traditionally-trained ballet dancers and Contact Improvisers, but also theatrically-trained and modern dancers in Karen Jamieson’s collaborative work Coming Out of Chaos in 1982.

Chapter One: Before Chaos is written by Emma Metcalfe Hurst, and edited by Charlotte Leonard.

![[L-R] Richard Fowler as Ama, Savannah Walling as Chamelea, and Terry Hunter as Drum Mother at the Aarhus Festuge, Denmark. 1985. Photograph by Jan Rüsz. Terry Hunter and Savannah Walling’s Terminal City Dance Collection.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6102f6fcb864c868a091548b/024e48b8-5227-4e70-a4c4-559c3ae95c3c/43-Terminal_City_1983_Drum_Mother_Hunter_01.jpg)

![[L-R] Peter Bingham, Jane Ellison, Linda Rubin, and others at Synergy Studio, Western Front. 1976. Photo by Daniel Collins. Linda Rubin, Synergy Movement Workshop Collection.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/6102f6fcb864c868a091548b/679b5eef-187a-406d-9523-8851f2f248f4/17+-+PeterBingham_JaneEllison_LindaRubin.jpeg)